A worker looks past a fence in a compound during a COVID-19 lockdown in the Jing’an district of Shanghai, China, on May 25, 2022. (Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

Is this more communist misdirection away from serious problems?

By Stu Cvrk

Commentary

State-run China Daily reported on June 20 that “the General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee has issued a regulation on the business activities of relatives of officials.”

While not fully explained, this appears to be the latest measure targeted at Chinese Communist Party (CCP) bureaucrats and apparatchiks in Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s decade-long anti-corruption campaign.

Is this announcement genuine or misdirection? Let us examine the topic in detail.

Anti-Corruption Campaigns

Anti-corruption campaigns are “a feature, not a bug” in communist regimes. Communist leaders frequently employ anti-corruption actions to divert domestic attention away from problems that are unsolvable—and exacerbated—by their socialist economic system.

Socialist systems invariably lead to shortages of the basic commodities and services needed for daily life in a civilized country, including food, shelter, fuel, medical services, housing, and consumer goods. Ubiquitous side effects of those shortages are the long queues that average citizens must endure to obtain anything and everything.

All communist countries have underground economies that involve de facto bribery to obtain basic necessities, goods, and services. A key aspect is the monetization of bureaucratic positions, as communist apparatchiks use their power and control to sell favors outside normal procedures to those who can pay—and who wish to avoid those infernal queues.

This is the very essence of corruption in a communist state. But that is just a symptom of the larger problem of graft and corruption in communist dictatorships.

The Soviet Union Example

It is axiomatic that when a communist leader publicizes an anti-corruption campaign, the initiative is intended to distract and misdirect citizens from far more serious problems and exert additional political controls on targeted groups.

The Soviet-era anti-corruption campaigns diverted public attention away from recurring famines due to failed harvests that resulted from collective farming and crackpot Lysenkoism, as well as from the aforementioned shortages.

As reported by the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Justice Programs in 1977, a Sovietologist estimated that economic crimes, such as bribery and corruption, amounted to 25 percent of all crimes committed in the Soviet Union.

That corruption even extended into factory operators who frequently faced problems obtaining the supplies needed to produce end-products; managers used the “blat” to fulfill the production requirements for their enterprises. “Blat” refers to “the use of personal influence to obtain certain favors to which production units are not legally entitled.”

Soldiers in Moscow look on at the funeral of Soviet leader and former KGB head Yuri Andropov in 1984. Seven years later, the Soviet Union collapsed. (AFP/Getty Images)

Corruption was essentially institutionalized as a fact of life in the old Soviet Union, and various Soviet leaders conveniently implemented anti-corruption campaigns to distract from the shortcomings of the Soviet economy and the daily hardships faced by Soviet citizens.

In one such campaign begun in 1983, Soviet leader Yuri Andropov even targeted his predecessor Leonid Brezhnev’s associates, although the purge also affected ordinary Russians, as reported by The New York Times in 1985: “According to news accounts, bank managers, collective farm chairmen, doctors, union officials, deputy ministers, a circus manager, and even some party officials are being sentenced, along with corrupt taxi drivers and checkroom and filling station attendants.”

The Communist Chinese Experience

Corruption is endemic and a serious problem in communist China. The book “Red Roulette: An Insider’s Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption and Vengeance in Today’s China” was published in September 2021. It provides special insight into the corruption of China’s ruling elite, including senior CCP members.

As noted by Publishers Weekly here, the author condemned “a political system that mouthed Communist slogans while … officials gorged themselves at the trough of economic reforms.”

Xi would appear to agree, at least in part. In a mixed message on June 17, as reported by Bloomberg, Xi “said corruption in the country remains severe and complicated even though progress has been made in the battle against graft” while “China’s Politburo declared its anti-corruption dragnet of financial institutions a success.”

Xi has made fighting corruption a centerpiece of his rule from the very beginning. In 2012, he charged the Central Commission for Discipline and Inspection (CCDI)—the agency tasked with battling corruption within the CCP—to aggressively pursue graft and corruption associated with the patronage system.

His goals were twofold: to consolidate his political power by pursuing “corrupt” factional rivals and to actually deal with continuing rampant corruption among CCP members and their economic allies.

According to The Washington Post, by 2018, the CCDI had “disciplined more than 1.5 million officials” since the beginning of the anti-corruption campaign. As a result, while corrupt actions of Party members may have been curbed over time, there have been two other by-products of that campaign: Xi has earned a degree of popular support for anti-corruption actions but has also alienated many Party members (especially his factional rivals).

In March 2018, Xi “convinced” the 13th National People’s Congress (China’s rubber-stamp legislature) to create a new anti-corruption agency called the National Supervisory Commission, which absorbed the CCDI and is headed by Yang Xiaodu, Xi’s close ally and aide.

The anti-corruption focus of the new commission was expanded beyond members of the CCP to include “managers of state-owned companies and institutions, including schools, universities, hospitals and cultural institutions.”

The new commission also focuses on maintaining ideological purity and, especially, political control, including general loyalty to Xi. Its evolution and inner workings are detailed here.

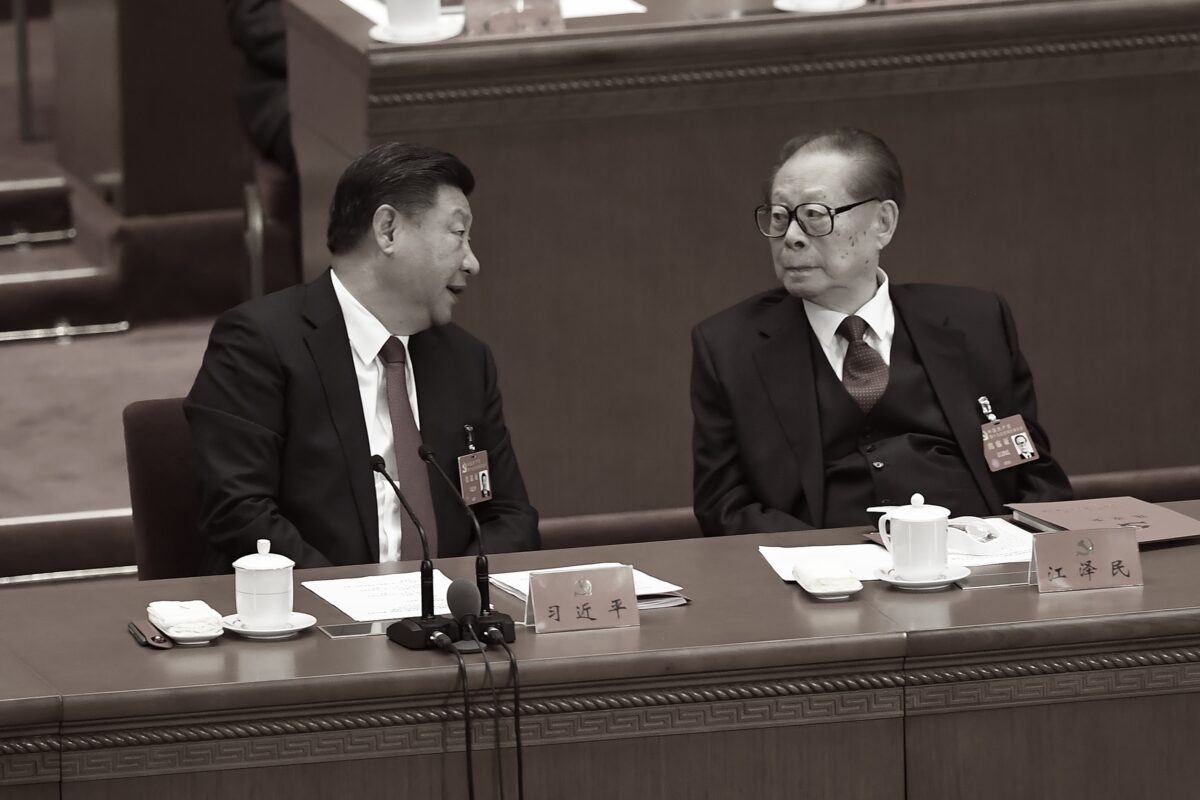

Xi has employed his anti-corruption campaign to punish Chinese billionaires aligned with his political rivals, particularly former leader Jiang Zemin’s faction.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping (L) talks to former leader Jiang Zemin (R) during the closing of the 19th Communist Party Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on Oct. 24, 2017. (Wang Zhao/AFP via Getty Images)

A key example has been the campaign against Ant CEO Jack Ma when Chinese regulators canceled the company’s dual IPO listing in Shanghai and Hong Kong in November 2020—it would have been the “world’s biggest-ever” IPO listing at $37 billion, according to Fortune.

Alibaba founder Ma was caught up in an anti-corruption probe of the former Party secretary of the technology hub of Hangzhou, Zhou Jiangyong. The investigation involved examining the extent of Ant Group’s transactions with state banks and enterprises, and resulted in a forced reorganization of the company.

No doubt at Xi’s insistence, the communiqué of the 6th plenary meeting of the 19th CCDI that was announced in January 2022 contained this anti-corruption gobbledygook and opiate for the masses: “The strategic determination of fighting corruption and punishing evil has focused on the overall situation of modernization, and played a role in supervising and ensuring implementation and promoting perfect development.”

The Supreme People’s Procuratorate work report at the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in March contained a sharp increase in bribery and corruption-related prosecutions in 2021, as reported by Sino Insider here: 23,000 cases (27,000 people) of corruption, bribery, and malfeasance; recovered 59.66 billion yuan of stolen funds and goods from official duty-related crimes; 13,000 cases of market manipulation, insider trading, illegal fundraising, money laundering, and other crimes; 134,000 people were prosecuted for crimes involving the disruption of economic order; 43,000 people were prosecuted for financial fraud and disrupting financial management order; 1,262 people were prosecuted for money laundering crimes; 9,083 people were prosecuted for accepting bribes and 2,689 people were prosecuted for offering bribes; 23 former provincial and ministerial level cadres were prosecuted, including Wang Fuyu and Wang Like.

In the background is a photo of Zhongnanhai, the central headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party, in Beijing. Two ministerial officials, Dong Hong (left) and Wang Fuyu (right) were given death sentences and suspended execution in January 2022. (Mark Schiefelbein/Pool/Getty Images/The Epoch Times Edit)

And then, there was Xi’s pledge made on June 17 during a group study session of the Political Bureau of the CCP’s Central Committee “to continue with a zero-tolerance attitude toward corruption, while reiterating the need to create deterrents, strengthen the institutional constraints and build up moral defenses among officials,” according to state-run media China Daily.

Xi speaking about anti-corruption efforts should be an automatic red flag for all China watchers. Why at this particular time? What might he be hiding? Is this more communist misdirection away from serious problems?

Here are some examples of real issues that this latest anti-corruption pronouncement from Xi could be meant to obfuscate:

- The ongoing bank runs: after years of communist rule and COVID-19 lockdowns, it appears a growing number of average citizens are losing trust in the country’s leaders and are afraid of losing their life savings.

- The forced “Zero-COVID” policy: lockdowns in Shanghai and other cities disrupted the Chinese economy and enraged those locked down at home for weeks.

- Real estate implosion: this manifested by the bankruptcy of property giant Evergrande and the associated debt bomb’s ripple effects throughout China’s economy.

- Faltering economy: the ongoing general implosion and collapse of the Chinese economy can no longer be hidden, as described in detail here by China expert Gordon Chang.

Conclusion

Anti-corruption campaigns are a feature of communist regimes, including communist China. Their purposes are three-fold: root out “corruption,” serve as a tool to exert and extend ideological and political control, and distract domestic audiences from serious problems.

A centerpiece of Xi’s 10-year rule has been a continuing anti-corruption campaign. There are plenty of economic and social problems in totalitarian China today, virtually all of which were brought about by the policies of the CCP itself.

Should Xi’s latest announcement about “zero-tolerance toward corruption” be taken at face value? Or is it a signal to anti-Xi factional rivals that they should either support Xi’s bid for an unprecedented third term as Chinese leader at the next Party Congress or else face yet another “anti-corruption clampdown”? Or is he trying to deflect attention from some intractable problems that his failed policies exacerbated? I vote all three.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NTD Canada.