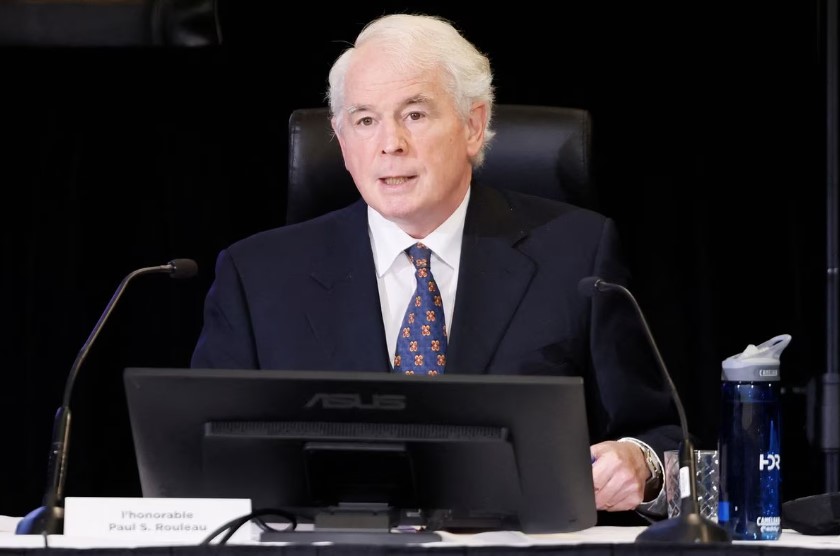

Justice Paul Rouleau speaks during the Public Order Emergency Commission in Ottawa, November 22, 2022. (REUTERS/Blair Gable)

By

Commissioner Paul Rouleau says the federal government was justified in invoking the Emergencies Act to clear convoy protests in February 2022.

“After careful reflection, I have concluded that the very high threshold required for the invocation of the act was met,” Rouleau said on Feb. 17 at a press conference after releasing the final report of the Public Order Emergency Commission.

“I have concluded that when the decision was made to invoke the act on Feb. 14, 2022, cabinet had reasonable grounds to believe that there existed a national emergency arising from threats to the security of Canada that necessitated the taking of special temporary measures.”

In his report, Rouleau, an Ontario appeal court justice, says he reached his conclusion with “reluctance,” as such emergency measures should only be used on rare occasions.

“It is only in rare instances, when the state cannot otherwise fulfill its fundamental obligation to ensure the safety and security of people and property, that resort to emergency measures will be found to be appropriate,” he wrote.

Police face off with demonstrators in Ottawa on Feb. 19, 2022. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

The inquiry was launched last year as required by law to evaluate the government’s use of the act to clear convoy protests. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau invoked the act for the first time since its creation in 1988 on Feb. 14, 2022, and revoked it on Feb. 23, 2022, once the protests in the nation’s capital were cleared.

The commission’s report was tabled in Parliament on Feb. 17.

Shortcomings

In the commission’s 2,000-page, five-volume report, Rouleau says there were a series of policing failures throughout the protests that led to the situation getting out of control.

“Lawful protest descended into lawlessness, culminating in a national emergency,” he wrote.

He also says what transpired throughout the events can be seen as a “failure of federalism.”

“In Canada, our federal system of government enriches democracy by striving to maintain national unity while supporting regional diversity. But fulfilling these promises depends on co-operation and collaboration,” the report says.

Rouleau also noted that the government’s messaging inflamed the protesters.

The report says that ahead of the convoy’s arrival in Ottawa, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Jan. 27 referred to the protesters as a “small fringe minority” who hold “unacceptable views” and who don’t “represent the views of Canadians.” It also made reference to a Jan. 31 press conference held by Trudeau in which he disparaged the protesters.

“This served to energize the protesters, hardening their resolve and further embittering them toward government authorities,” Rouleau wrote.

Rouleau said he expects that Trudeau was referring to a “small number of people who were expressing racist, extremist, or otherwise reprehensible views” rather than all protesters. But he says political leaders from different levels of government should have made more effort to acknowledge that the majority of the protesters were exercising “their fundamental democratic rights.”

“The Freedom Convoy garnered support from many frustrated Canadians who simply wished to protest what they perceived as government overreach,” he said.

“Messaging by politicians, public officials and, to some extent, the media should have been more balanced, and drawn a clearer distinction between those who were protesting peacefully and those who were not.”

Rouleau also said that while he found that the measures taken by the federal government were for the most part appropriate, there were deficiencies, including how it implemented its requirement for freezing financial assets of protesters.

“[This included] the absence of any discretion related to freezing assets, and the failure to provide a clear way for individuals to have their assets unfrozen when they were no longer engaged in illegal conduct,” Rouleau said at his press conference.

National Emergency

The Emergencies Act requires that before it can be invoked, there needs to be a threat to the security of Canada. This threat needs to be so serious as to be considered a national emergency. As to how this threat is defined, the act references the definition of “threats to the security of Canada” in the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) Act.

The CSIS Act definition provides four categories of threats: espionage and sabotage, foreign-influenced activities, threats or acts of serious violence with ideological motives, and violent revolution.

Some of the opponents of the government’s use of the act throughout the commission made reference to this definition, saying that none of these conditions were present during the protests.

The head of CSIS, David Vigneault, made a similar assessment as far as the determination of the presence of a national emergency according to the CSIS Act is concerned.

“We did not make a determination that the event itself” was a threat to national security, Vigneault told the commission on Nov. 21.

RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki made a similar statement to the commission on Nov. 15.

However, Rouleau noted that Justice Minister David Lametti told the inquiry on Nov. 23 that the decision-making on the use of the act doesn’t rest with the CSIS, but with the government, and that the government uses a “wider set of criteria by a very different set of people with a different goal in mind” to make its interpretation of the threats present.

Rouleau noted the incident at the border crossing in Coutts, Alberta, where the RCMP arrested 13 people on weapon charges, some of whom were charged with conspiracy for murder of RCMP officers. Shortly after this incident, protesters cleared the Coutts blockade, saying that they didn’t want to be associated with the group that was arrested, and wanted to maintain their peaceful image.

“The fact that this situation was discovered and disrupted is a credit to law enforcement. It was, nevertheless, clearly a situation that could reasonably be viewed as meeting the definition under section 2(c) of the CSIS Act, but that CSIS had not identified as such,” Rouleau wrote.

Section 2(c) of the CSIS Act states: “activities within or relating to Canada directed toward or in support of the threat or use of acts of serious violence against persons or property for the purpose of achieving a political, religious or ideological objective within Canada or a foreign state.”

The government of Alberta, which argued against the use of the Emergencies Act during the inquiry, said that the fact that the Coutts blockade was cleared without the use of the act was testament to the fact that its use wasn’t needed. Other provinces with the exception of Ontario, B.C., and Newfoundland and Labrador, also weren’t fully on board with the use of the act. The Ontario Provincial Police, which coordinated the clearance of the blockade at the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor and was also involved in policing protests in other parts of the province including Ottawa, also argued at the commission that the Emergencies Act wasn’t needed.

Referencing the Coutts incident, Rouleau said that the federal government could “reasonably consider that the risk of similar groups of politically or ideologically motivated violent actors being present at other protests met the definition in section 2(c) although CSIS had not identified them.”

He said that while it’s possible that serious violence could have been avoided without the use of the act, that still doesn’t make the decision to use the act a wrong one.

“There was an objective basis for Cabinet’s belief, based on compelling and credible information. That was what was required. The standard of reasonable grounds to believe does not require certainty.”

Rouleau made a number of recommendations to modify the Emergencies Act, including removing the reference to the CSIS Act on how to define threats.

Not Binding

Rouleau said that his report is not binding on the courts that could be hearing cases against the government’s use of the act.

“I do not come to this conclusion easily. As I do not consider the factual basis for it to be overwhelming, reasonable and informed people could reach a different conclusion than the one I have arrived at,” he said at the press conference.

Several civil liberties groups as well as the province of Alberta are currently challenging the use of the act in the courts.

The convoy protest started in January 2022 as a demonstration by truck drivers opposed to the government’s requirement that cross-border truckers had to be vaccinated for COVID, but became a huge movement as large numbers of people from across the country joined the cause to remove all pandemic mandates and restrictions.

Convoys of protesting trucks and vehicles first converged in Ottawa in late January 2022, with many parking in the Parliament Hill area. As the protesters remained encamped in Ottawa into February, similar protests arose at border crossings, including at the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor, the border crossing near Coutts, Alberta, and the Emerson border crossing in Manitoba.

The protest in Windsor was cleared using regular police enforcement before the Emergencies Act was invoked, and the protesters in Coutts and Emerson voluntarily dispersed without the use of the act.

‘Once-in-a-Generation Crisis’

During the press conference, Rouleau noted that COVID-19 presented a “once-in-a generation” crisis that the different levels of the government attempted to respond to “in good faith circumstances as they understood them.”

Police begin to break up protesters opposing COVID-19 vaccine mandates in Ottawa on Feb. 18, 2022. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

But he noted that regardless of how the health measures imposed by the governments may be viewed, they imposed hardships on many Canadians, causing many to lose their jobs, businesses, homes, and savings.

He said that the truckers were among the groups who “felt a heavy weight from the pandemic,” whose hardship was made more difficult at times by health orders.

“When new rules that limited the ability of the unvaccinated truckers to cross the Canada-U.S. border were announced [on Jan. 15, 2022], this served as a rallying point for those who disagreed with government policy,” he said.

The result was that many in Canada mobilized to form the Freedom Convoy, he said.

“It’s hardly surprising that government health measures would cause some form of protest in response, given their impact on people’s lives,” Rouleau said.

“What was surprising was the size and scale of these protests and the way in which they proliferated across the country.”

Rouleau said the majority of the protesters wanted to engage in peaceful demonstrations, but said there were some who had ulterior motives and were willing to engage in dangerous acts.

“[The protests] ranged from peaceful marches to blockades of critical infrastructure,” he said. “The size and scope of these protests was truly unprecedented. Police and governments alike struggled to respond.”

Noé Chartier contributed to this report.