Domtar’s pulp and paper mill at Crofton, B.C., on Jan. 30, 2026. Paul Rowan Brian/The Epoch Times

It marks the end of an era for the mill, which opened in 1957 and went on to employ thousands, anchoring the local economy and feeding into the broader forestry sector.

After notice of the mill’s closure was issued Dec. 2, 2025, and operations shut down in early February, about 350 mill jobs were lost, and hundreds more jobs in related industries put at risk.

The closure is part of a broader wave of mill shutdowns in B.C. as operations struggle to remain economically viable. The closures have led to mass layoffs, devastating local families and communities, and negatively impacting secondary industries and the surrounding economy.

Hélène Marcoux, research director at the University of British Columbia’s Malcolm Knapp Research Forest, said B.C.’s forestry industry is being undercut by an increasingly competitive global market.

“Our cost of producing, or our cost of running these mills, is increasing, and we can’t compete in major markets,” she said in an interview.

Marcoux said the industry has also been hit by other damaging factors, including a mountain pine beetle infestation that peaked between 2004 and 2009 and destroyed vast swaths of timber. The provincial forestry ministry estimates the beetle wiped out 140 million cubic metres of pine in 2004 alone.

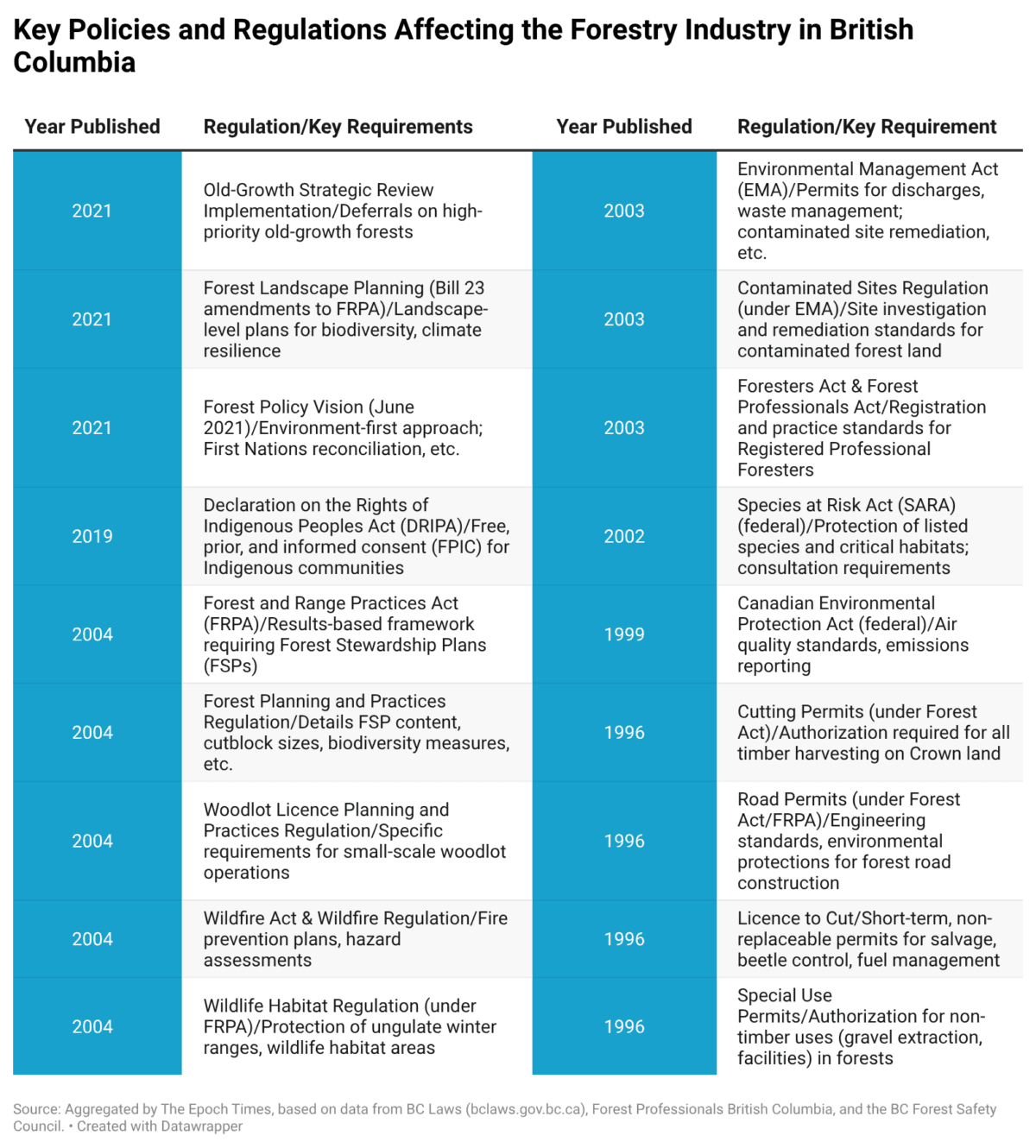

Meanwhile, University of Victoria professor emeritus of economics Cornelius van Kooten says increased regulations as well as U.S. tariffs are adding to the challenge.

Economic Impact

In addition to those who have lost their jobs directly, the mill’s closure is projected to lead to considerable lost municipal revenue and cause ripple effects furthering economic decline in the small mill town.

Rob Douglas, mayor of North Cowichan, which includes Crofton, has said he expects the closure to cost $800,000 in lost industrial taxes this year alone.

For many of the workers who are now left to find new employment, the situation is daunting.

Taylor LaForge, 32, who worked in the plant’s digester and bleaching division, said he’s in a sound position financially and has plans to retrain in a trade such as plumbing or HVAC work. But he said many of his coworkers are in a much more precarious position.

“One guy’s got a mortgage, a one- or two-year-old daughter, and another kid due in two months,” he said. “A lot of us don’t have transferable skills or trades that we can fall back on.”

During his last 60 days on the job, LaForge said he found himself feeling sad about leaving behind the good friends he’d made there, but felt most worried about the fate of coworkers who didn’t know what they would do next.

Another worker, David, told The Epoch Times that he did seven 84-hour work weeks in the lead-up to his last day on Feb. 3, to try to make as much money as he could before being out of work. He asked that his real name not be used so it doesn’t affect his relations with the company as he negotiates a severance package.

“I’m going to run myself ragged,” he said, “And then in the end I’m still gonna be out of a job.”

David’s frustration isn’t only about where his next paycheque will come from, it’s about what he will do with his life and what career he can transition into in order to provide for his wife and two young children.

His past experience on oil rigs, at other sawmills, and years spent offloading the payloader at the Domtar mill have given him a broad skill set and the endurance required for physically demanding work. But he lacks the certifications needed to transition easily into another career, he said.

The Impact Chain

Mills like the one in Crofton are part of B.C.’s integrated coastal forestry system, where logs are processed at sawmills, the leftover byproducts of bark and chips are sent to mills for fibre, and that fibre is then used to make paper and packaging products.

The shuttering of the mill has had a domino-like affect on the nearby Atli Chip Plant. The First Nations majority-owned plant near Port McNeill on northern Vancouver Island announced in late January that it will close next month due to a lack of demand for the chips it produces.

There have been 21 permanent and indefinite mill closures since 2023 and 15,000 forest sector jobs lost since 2022, according to the Council of Forest Industries.

“If you lose the pulp mill, the sawmills have no way to dispose of the byproduct,” Marcoux said. “They have no solution, and now [they] are overwhelmed with waste … Now they have to pay to dispose of it.”

Van Kooten says B.C.’s forestry sector is grappling with two main challenges. One, he said, is the impact of government regulations, including “environmental, indigenous issues, restrictions on log exports.” The other, he said, is the ramification of U.S. trade tensions.

“The current issue, and the one leading to mill closures, relates to the latter,” he told The Epoch Times.

B.C. Premier Eby ha said in the past that U.S. tariffs and declining lumber prices are to blame for the rash of closures happening in the province, calling tariffs an “existential threat” to mills across the province and the forestry industry as a whole.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade measures on Canadian softwood lumber, including additional tariffs under national‑security rules, have pushed total duties—comprising anti‑dumping, countervailing, and other levies—toward roughly 45 percent for many Canadian producers.

As U.S. tariffs rise, many companies reduce timber harvesting even further, leaving sawmills with less wood. Diminished raw material means mills have less wood fibre to work with and some are forced to close, disrupting the steady supply the mills would have needed to stay open. Coupled with already high logging costs, permitting delays, and privately held land incentivized by high global prices to sell abroad, the integrated economy begins to unravel as the fibre supply steadily dries up.

U.S. duties are not the only problem the industry has to contend with. Marcoux also pointed to other products like two-by-fours, plywood, and processed timber that are being overtaken by cheaper labour and harvesting costs in other places.

She said the southeast United States serves as an example where the rapidly growing and easily harvested Southern Yellow Pine has emerged as North America’s leading timber. Brazil also exports massive amounts of pulp and timber worldwide.

Since Canadian companies need to compete in the global market, Marcoux said, “If the price is set by the global market, and now if our costs to run these mills and facilities are increasing, for lots of different reasons, it’s hard to compete.”

‘Heartbreaking’

North Island—Powell River Conservative MP Aaron Gunn called Atli’s closure “heartbreaking” in a Jan. 21 X post and blamed it on provincial government policies in delaying permits and imposing restrictions.

B.C. allows 60 million cubic metres of timber to be cut each year, but the actual amount harvested has been roughly 30 million cubic metres per year for the last several years. Premier Eby tasked B.C.’s Minister of Forests Ravi Parmar last year with bringing that amount up to 45 million cubic metres per year, but it only hit 32 million cubic metres.

“My plans will include transitioning us away from cutting permit forestry to full operational planning forestry,” Parmar said at a logging convention recently. “I see a future where we have no need for cutting permits in forestry here in British Columbia.”

Marcoux said while overall raw log exports from B.C. haven’t increased in recent years, it can be a problem in some areas such as Crofton where private companies would rather ship raw logs abroad and get higher prices for them than send them to sawmills.

“At the end of the day, a lot of this is about money and being competitive and being able to operate in global markets,” Marcoux said.

She added that permitting delays have played a large role, making it hard for companies to respond to market changes and remain profitable.

“You’re waiting for months and months, maybe a year, even more, to get cutting permits. So as a logging contractor, as a sawmill, anyone who’s involved in this work, you can’t be responsive to markets,” she said. “It’s hard to be responsive and be nimble. So I think that that’s a big problem as well.”

Eby said in January that significant reforms will be made that will lead to a better future for forestry in B.C.

“It always feels too slow for the urgency of the crisis facing the sector right now,” Eby said. “But predictable land access, permit reform, value-added investments and new trading relationships will deliver a better forestry future.”

The B.C. Council of Forest Industries (COFI) has said that many of the deepest challenges facing the province’s forestry sector could be corrected by the province.

Specifically, COFI wants the government to speed up cutting permits, road approvals, and reducing regulatory red tape for mills.

“Instead of realizing the full potential of BC’s world-leading forest products, we are continuing to lose ground domestically and globally as [the] highest cost jurisdiction in North America,” the organization said. “But we need the province to step up now.”