Lawyer Xie Yang (center) and his client Xu Yan (right), wife of human rights lawyer Yu Wensheng, try to meet with Yu outside the Xuzhou Intermediate Court in Xuzhou, in eastern China’s Jiangsu Province, on Oct. 31, 2019. (Nicolas Asfouri/AFP via Getty Images)

New revelations indicate China’s system of secret RSDL jails reached 100,000 victims

By Peter Dahlin

News Analysis

On the eve of Jan. 11, former lawyer and human rights defender Xie Yang was on a video call with Lyndon Li, a Chinese law student in England, when police suddenly appeared at his home, and the call ended abruptly.

The news leaked out within a few days that Chinese authorities had taken Xie away—this was not the first time.

Xie shot to fame after spending six months inside China’s system for secret jails or Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). He described in detail to his lawyers the prolonged, severe physical and psychological torture he had experienced inside the system.

As Xie’s testimony made headlines worldwide, China’s RSDL was not widely known until that point. Many other lawyers, alongside Xie, who were also placed into the RSDL system around the same time, have helped to slowly expose it as more victims came forth willing to speak about the reality behind those four letters.

The Dual Rise of Xi Jinping and RSDL

The RSDL system was put into place as Xi Jinping took power, and it has expanded in scope and size alongside the leader’s growing control over Chinese society.

RSDL allows the police to take any target(s) off the street, place them inside solitary confinement at secret locations, hold them incommunicado, and deny their family or anyone else knowledge of their whereabouts. It is essentially legalized kidnapping, and the United Nations has stated as much, if in more diplomatic language.

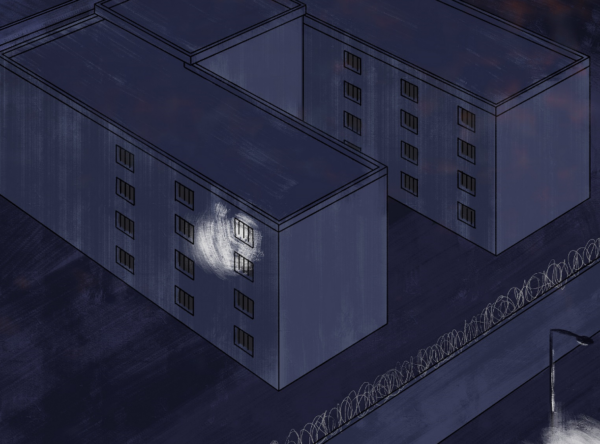

A drawing of an RSDL facility in southern Beijing by Antlem. (Courtesy of Peter Dahlin/Safeguard Defenders)

Around the time of the Winter Olympics in Beijing this year, court data (some of which are available online in a database hosted by China’s Supreme Court) revealed that RSDL remains extensively used. During the pandemic, against all odds, its use increased even more. The RSDL may now have claimed as many as 100,000 victims, the equivalent of 150 Guantanamo Bays.

The first known victim, Zhu Chengzhi, was put in the RSDL on Jan. 4, 2013, within the first three days the system was first put into use. Zhu happens to be from the same province as Mao Zedong, a man to whom Xi is often compared. Zhu would later claim another distinction; in mid-2018, he became the first known victim to be placed into the system a second time.

It wasn’t always like that. In the same year that Zhu became RSDL’s first victim, there were close to 1,000 victims nationwide. At the time, RSDL was primarily used in exceptional circumstances; for example, when an individual couldn’t be arrested due to illness or detention made it challenging to carry out an investigation. But gradually, the lack of oversight allowed the Chinese police to abuse the RSDL system.

By the time the “709” crackdown started in 2015, a nationwide campaign that targeted human rights lawyers, the use of RSDL had grown significantly. A year or two later, sources showed that local police started using the system indiscriminately against those charged with minor and regular crimes.

Lawyers and activists gather for a silent protest at the court of final appeal in Hong Kong for the fourth anniversary of the “709” crackdown on human rights lawyers across China on July 9, 2019. (Anthony Wallace/AFP/Getty Images)

With RSDL, the Chinese police have expanded their power significantly and in a way that undermines more or less every basic rights one has come to expect. Those placed into RSDL cannot be held in detention centers, police stations, or anything deemed a “case-handling area.” Instead, police can use either custom-built facilities, for example, secret jails and renovated rooms in controlled facilities such as guest houses, training centers, etc.

Once taken into RSDL, one simply disappears.

To make matters worse, a victim can be held under the system for six months. Once inside the RSDL, the law states that individuals must be kept in solitary confinement and in facilities designed to protect them from self-harm. In short, suicide-padded, solitary confinement cells.

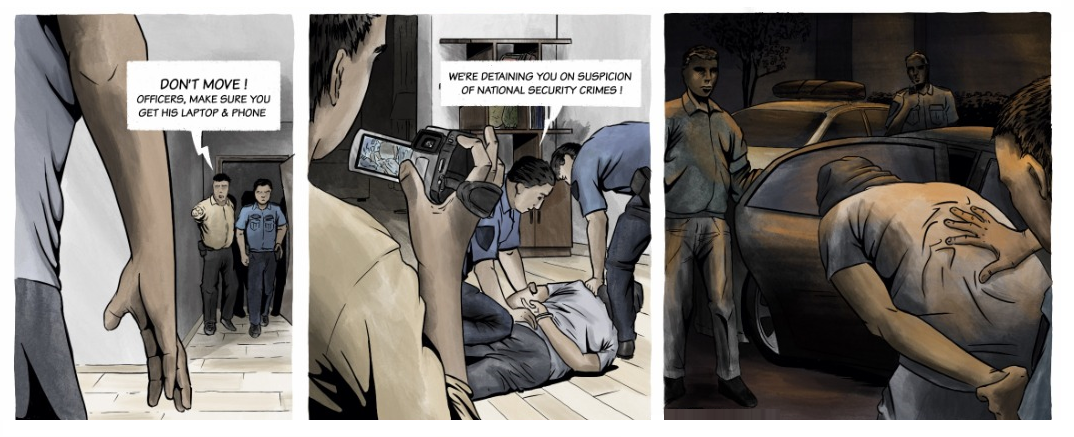

A drawing of police raiding a victim’s home and taking him into RSDL by Antlem. (Courtesy of Peter Dahlin/Safeguard Defenders)

This absolute power that RSDL affords police over its victims has not been lost on local police forces, who have taken up the use of RSDL with enthusiasm, which would explain its rapidly expanding deployment in recent years.

How One Man’s Testimony Exposed the Realities of RSDL

Xie’s testimony was the first detailed account of what goes on inside RSDL and revealed why it had become the preferred tool of the Chinese authorities. Why detain (bound by supervision and regulation) an individual when they can instead disappear (and act with impunity)?

For Xie, it began like many other days. One morning, he had left to travel out of town to represent a group of farmers over a land dispute.

A photo of Xie Yang in 2021. As one of the lawyers victimized during the “709″ crackdown, Xie was recently abducted by Chinese state security. (Provided by Chen Guiqiu)

“There was nothing different about this time. Like before, he left for work,” his wife, Chen Guiqiu, told this author.

Two days later, while he stayed at a hotel out of town, he was awoken before daybreak by a large group of both plain-clothed and uniformed officers who took him away. Within 24 hours, Xie was officially placed under RSDL, and authorities told him: “Your only right is to obey,” according to author Michael Caster.

In reality, the police can do anything under RSDL, short of killing a person, as they have six months of total control over their victim.

A doctor attending to those who disappeared under RSDL put it plainly once: “Don’t let them die. A dead person would create big problems. Someone who is only injured doesn’t matter,” according to a report by Human Rights Watch.

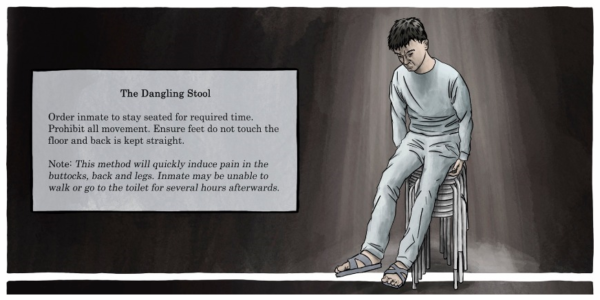

Six months of torture would follow. Through it all, interrogations, which often occurred while the victim was shackled to a tiger chair, would happen frequently. At some point, Xie thought some 40 different people had interrogated him. He was deprived of sleep and spent up to 20 hours a day on the “dangling stool.” It is a small, narrow, high stool where the victim’s legs cannot reach the floor. Slowly, over hours, blood gets cut off from the legs, causing intense, crippling pain. This would be alternated with being kicked, kneed, punched, or hung from the ceiling and beaten unconscious.

An illustration of torture with “dangling stool” by Antlem. (Courtesy of Peter Dahlin/Safeguard Defenders)

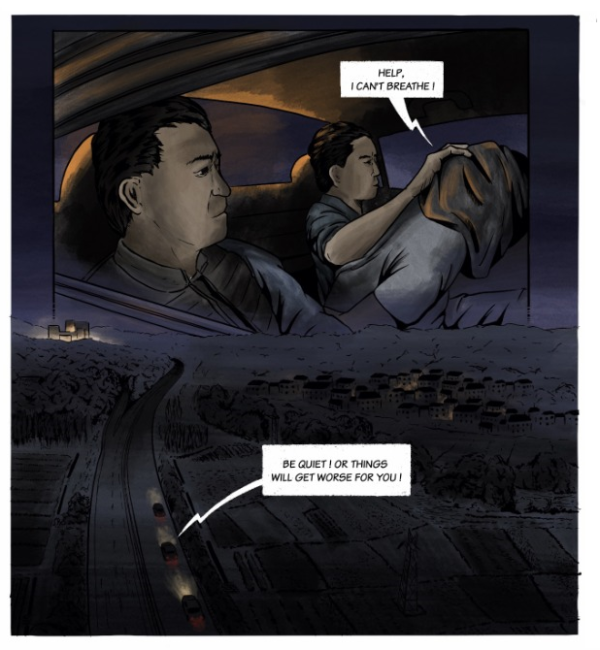

Death threats were common. According to Caster, one person, a middle-class, white-collar IT engineer, was threatened before even arriving at the custom-built RSDL facility in southern Beijing. He was told: “We are crossing the mountains. If you want to come back alive, you should think well about what you tell us.”

A victim is threatened while being taken to an RSDL facility in southern Beijing. (Courtesy of Peter Dahlin/Safeguard Defenders)

Of course, not everyone suffers the same abuses. A young man from northeastern Dongbei—China’s rust belt—said he was stripped naked in his cold cell, with extra guards brought into the room, and then told to stand on one leg and sing the Chinese national anthem.

Xie might have avoided the same fate as Zhu, who was taken into RSDL a second time, but that is precisely what happened to fellow lawyer Chang Weiping not long before the police took Xie away.

Chang spent nearly half a year inside RSDL before being arrested; he is now awaiting trial. So far, no one knows what Chang has had to go through.

Chinese rights lawyer Chang Weiping’s parents protest the torture of their son in front of the Gaoxin branch of the Baoji City Public Security Bureau, China, on Dec. 14, 2020. (The Epoch Times)

Raising Awareness of RSDL

Many lawyers, journalists, non-governmental organization (NGO) workers, and others who work in sensitive fields and are often targeted by authorities were oblivious to the system for quite some time. Those who heard about RSDL often thought it was a mild form of detention, something less severe.

When co-workers of Wang Quanzhang, another well-known rights lawyer, learned that he had been placed into RSDL instead of being arrested, they felt relief and thought it was a good sign. I was one of those colleagues with that very same thought.

For better or worse, those days are long gone within China’s rights defense community. RSDL has become as feared a tool as they come. As what goes on inside leaks out, the community has been given a wake-up call. The worse the stories that leak out, the more RSDL terrifies the larger community. It has, in effect, become a tool of political terror.

Wang Yu, a lawyer, didn’t know much about RSDL until she was held in a secret jail for six months. Her husband, Bao, a local activist, went through the same ordeal. But torture wasn’t enough to break them.

Police went further and threatened to arrest the couple’s then-teenage son, Bao Mengmeng. He made headlines worldwide when he was captured by Chinese police inside Burma (commonly known as Myanmar), alongside two activists trying to smuggle him out of China after his parents had been disappeared. Those two activists were taken back to China and likely placed into RSDL, while Mengmeng spent about two years under police custody until 2018.

The True Scope of China’s Use of Disappearances via RSDL

In 2018, the United Nations Human Rights Council condemned China’s RSDL system and called for its complete abolishment. However, until early 2020, there had been no attempts to figure out the extent to which the system was used. That changed with a small report, a data analysis from the NGO Safeguard Defenders, which showed how it is possible to track the use of the system—by using China’s public database on verdicts.

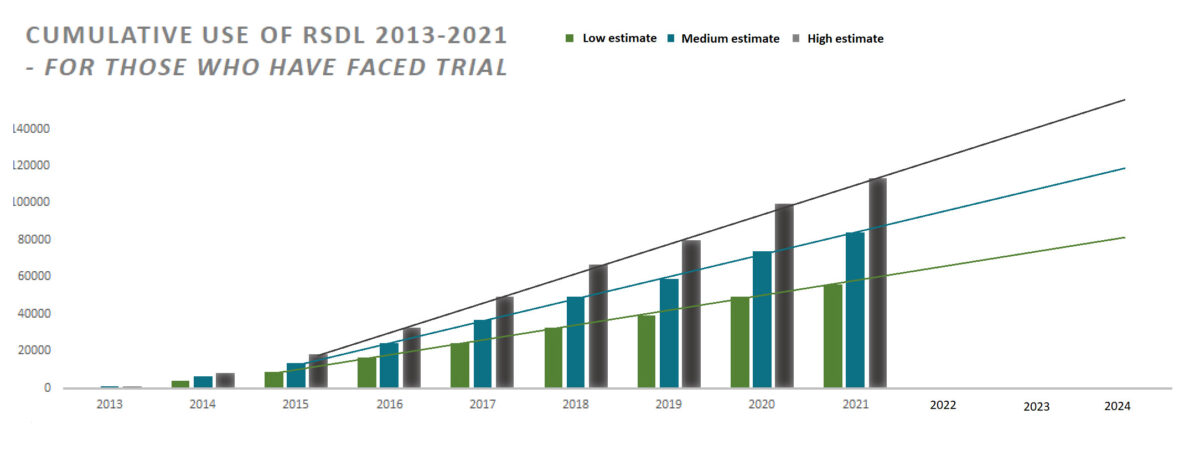

Now, some two years later and after a new round of research from the database China Judgments Online, more information on the scope and scale of the system can be presented—and it is grim reading. As with any statistics in China, the data is flawed at best. In addition, thousands of verdicts mentioning RSDL use have been removed from the database, and more are disappearing almost every day as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tries to hide such information.

Despite that, and using knowledge derived from detailed studies on how RSDL cases are published, or not published, even such studies carried out by pro-CCP legal scholars in China, one can get a strong idea of how the RSDL system has developed.

(Courtesy of Peter Dahlin/Safeguard Defenders)

As clearly indicated by the U.N. in its condemnation of the RSDL system, its use often constitutes enforced disappearances, as the location of the victim is kept secret. Torture is rampant, and in addition, using solitary confinement for prolonged periods for interrogation purposes is in itself an act of torture.

This qualifies China’s use of RSDL as a crime against humanity on at least two points, if proven to be systematic or widespread, according to the aforementioned author Michael Caster, who is also an international law analyst and co-founder of Safeguard Defenders.

Furthermore, the consistent year-by-year data available on RSDL use, Safeguard Defenders spokesperson Laura Harth says, shows beyond doubt that it is both systematic and widespread.

For 2020, the last year for which more complete data exists, the RSDL system reached new heights, with some 15,000 new victims that year alone. For 2021, the figure remains high, at over 10,000, yet it may be too early to properly assess the data. By now, the system is likely to have seen anywhere from 85,000 to 115,000 victims.

The real problem with the aforementioned data is that they only scratch the surface. Many of those named in this article did not go on trial and were released often “under bail.” Such cases simply won’t show up in the database or anywhere else. It is impossible to know how much of the iceberg we are seeing in the data above, but most likely a big part is underwater.

RSDL Is Here to Stay, May Expand Beyond China’s Borders

The growing awareness of the CCP’s use of “hostage diplomacy” has centered on RSDL. Just like families are denied knowledge of victims’ whereabouts, so are foreign governments when their citizens are placed into the system. Whether it is British Lee Bo who was kidnapped in Hong Kong, Swede Gui Minhai who was kidnapped in Thailand, Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, or American basketball player Jeff Harper, among others, they were all quickly placed into the RSDL system.

With a more aggressive communist China—more willing to detain foreign citizens to get what it wants—every indicator points toward foreigners becoming a more common target for RSDL.

Members of the pro-democracy Civic Party carry a portrait of Gui Minhai (L) and Lee Bo during a protest outside the Chinese Liaison Office in Hong Kong on Jan. 19, 2016. (Bobby Yip/Reuters)

Worse yet, according to Harth, is “the deafening silence from Western governments about the system and its rapid expansion. … The complete lack of any political cost imposed on the Chinese Communist Party for engaging in what is clearly yet another crime against humanity sends a clear-cut message to other authoritarian governments, especially in Southeast and Central Asia” and “who study China’s methods to silence dissent,” that may adopt similar “legalized” forms of disappearances.

Even though disappearances never went away, since its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s, it has become an anomaly and was used mostly on an ad-hoc basis, as it had become a crime, like torture, considered so heinous that even the worst dictatorships at least pretended to not engage in it.

With China’s “legalization” of disappearances and normalizing it by expanding its use to mass scale, the international human rights system stands before yet another challenge: how to fight back against such normalization.

“How many other countries can adopt similar systems until the norm is broken?” said Caster. “Will we see it spreading to other parts of the world, moving from authoritarian to authoritarian-leaning or ‘illiberal democracies’”?

There is far more at stake here than “merely” the abusive treatment of Chinese human rights activists.

With stronger pressure from the central government to maintain stability, lawyer Wang Quanzhang believes local governments are encouraged to use any means necessary, and RSDL is an easy, yet very powerful tool for just that purpose. It took a long time and ever-mounting criticism to get the CCP to abolish the reeducation through labor system. But it may take a lot more to get the CCP to abolish the RSDL system.

Until then, RSDL will continue to expand. It will be used to destroy Chinese civil society and, sooner or later, start spreading beyond China’s own borders.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NTD Canada.

Peter Dahlin is the founder of the NGO Safeguard Defenders and the co-founder of the Beijing-based Chinese NGO China Action (2007–2016). He is the author of “Trial By Media,” and contributor to “The People’s Republic of the Disappeared.” He lived in Beijing from 2007, until detained and placed in a secret jail in 2016, subsequently deported and banned. Prior to living in China, he worked for the Swedish government with gender equality issues, and now lives in Madrid, Spain.