A staff member wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) directs drivers as they check people’s nucleic acid test results and health codes at a highway toll station in Yantai, Shandong Province, China, on March 16, 2022.(STR/AFP via Getty Images)

By

The Chinese regime is using COVID-19 control measures to stop depositors whose savings were frozen by rural banks from protesting.

Several depositors told The Epoch Times on June 14 that the health code on their COVID-19 app turned red as soon as they scanned venue barcodes at Zhengzhou, the provincial capital city of central China’s Henan Province. A red health code—indicating a potential COVID-19 patient—means that the carrier is barred access to all public places from public toilets to shops to train stations and faces mandatory quarantine in centralized isolation centers.

They’re among tens of thousands of bank depositors who have fought to recover their savings for more than two months. The crisis started in April, when at least four lenders in Henan froze cash withdrawals, citing internal system upgrades. But customers said neither these banks nor officials have since offered any information on why or how long the process would take, prompting angry protests outside the office of the banking regulator in Zhengzhou in May.

An estimated 1 million customers were reportedly affected, which has left many residents’ life savings at stake and patients unable to pay for regular medical care.

Depositors have been cut off from at least 39.7 billion yuan ($5.91 billion), according to Sanlian LifeWeek, a state-run magazine.

Aggrieved depositors across the country planned another protest in Zhengzhou on June 13 to demand an answer, although previous gatherings were met with silence from local authorities and violence from plainclothes police officers.

Red Code

However, their plan was thwarted again as their health codes turned red at the city’s train stations or highway entrances.

A red code indicates the highest level of risk, meaning the person tests positive, has been close to a COVID-19 patient, or has visited high-COVID-risk areas in the past 14 days. Residents with a red code face two weeks of centralized isolation.

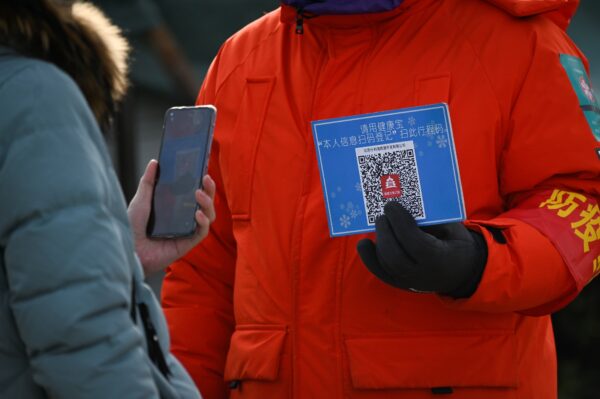

The Chinese regime adopted three-tiered color-based QR code systems utilizing big data and mobile technology to track people’s movement as part of its COVID-19 control measures. Residents must present a green health code on mobile phones while scanning a venue code for every place they visit.

A woman uses her cellphone to scan a venue code before entering an outdoor ice rink in Beijing on Jan. 12, 2021. (WANG ZHAO/AFP via Getty Images)

Liu Yong (pseudonym), a depositor from nearby Hebei Province, drove to Zhengzhou hoping to get his money back on June 12. But he ended up stranded on a highway as his health code turned red when he scanned the venue code at the exit.

Liu carried a green health code as well as a negative PCR test result when he left his hometown. He was required to return home, as police threatened to send him to a quarantine center if he refused to do so.

With the red code, his return road was blocked. Liu was unable to take a break or even use the toilets at the service station while driving back to Hebei. In an interview with The Epoch Times on June 14, Liu said he was still blocked at a highway exit leading to his hometown.

It was unclear how many people encountered the same issue, but one person involved told The Epoch Times that hundreds of depositors across the country shared their red code screenshots in a group chat on WeChat, the country’s popular instant message app.

An employee handling the Zheng Health Commission inquiries told The Epoch Times that they had heard of the health code problems and reported the issue to relevant departments.

Customers of the four banks in Henan Province hold papers that read “Henan banks return my deposits” in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China. (Provided to The Epoch Times)

Another bank customer, Li Yin (pseudonym), said she and three other depositors found that their health codes turned red when scanning Zhengzhou venue codes remotely on June 12. They tested the app in their homes in Inner Mongolia, a northern Chinese province that’s 550 miles away from Zhengzhou.

But Li said her friend’s husband, who wasn’t connected to frozen deposits, didn’t find the color change after scanning, adding to speculation that they were on authorities’ target list.

“They [officials] are like robbers,” said a third bank customer who was stopped by police at Zhengzhou train station on June 12 and required to leave. “We’re all legal depositors. Why couldn’t we even have an explanation?”

‘Digital Handcuffs’

Reports about depositors’ experiences by Chinese media went viral on the microblogging website Weibo on June 14 and provoked a public outcry.

The news fueled concerns that COVID-19 curbs were used by the Chinese Communist Party to strengthen social controls. Human rights lawyers and activists had previously told The Epoch Times that the regime abused health code apps to stop them from traveling.

Hu Xijin, a former editor of the CCP’s Global Times, wrote in a post saying that meddling with health codes for purposes other than pandemic prevention will jeopardize the authority of the system and public support.

“It’s so scary,” one user wrote. “If the health code is abused … it could be putting digital handcuffs on us. Everyone will become a prisoner from now on and could be stopped anywhere, anytime.”

Zhao Fenghua, Gu Xiaohua, and Luo Ya contributed to the report.