Chloe Cole was 15 years old when she agreed to let a “gender-affirming” surgeon remove her healthy breasts—a life-altering decision she now deeply regrets.

Her “brutal” transition to male from female was anything but the romanticized “gender journey” that transgender activists and medical professionals had portrayed, she told The Epoch Times.

“It’s a little creepy to call it that,” she said.

Cole, who is now 18, feels more like she’s just awoken from “a nightmare,” and she’s disappointed with the medical and school system that fast-tracked her to gender transition surgery.

“I was convinced that it would make me happy, that it would make me whole as a person,” she said.

Although she feels “let down” by most of the adults in her life, she doesn’t blame her parents for following the advice of school staff and medical professionals, who “affirmed” her desire for social transitioning, puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery.

Most of the medical professionals did nothing to question or dissuade her or her parents, she said.

“They effectively guilted my parents into allowing them to do this. They gave them the whole, ‘Either, you’ll have a dead daughter or a live son,’ thing. They cited suicide rates,” she said. “There is just so much complacency on the part of educators—all the adults basically. I’m really upset over it. I feel a little bit angry. I wasn’t really allowed to just grow.”

Her parents, though skeptical, trusted the medical professionals and eventually consented to their daughter’s desire for medical interventions, including surgery, which was covered by their health insurance policy.

“It shouldn’t be put on adolescents to make these kinds of decisions at all,” she said.

Transgenderism

Transgenderism, while widely celebrated in popular culture and on social media in recent times, is a much more divisive issue than people may think, Cole said.

Today, Cole is one of a growing number of young “detransitioners” who reject current trends in transgender ideology and oppose the “gender-affirming” model of care being pushed by progressive lawmakers at state and federal levels.

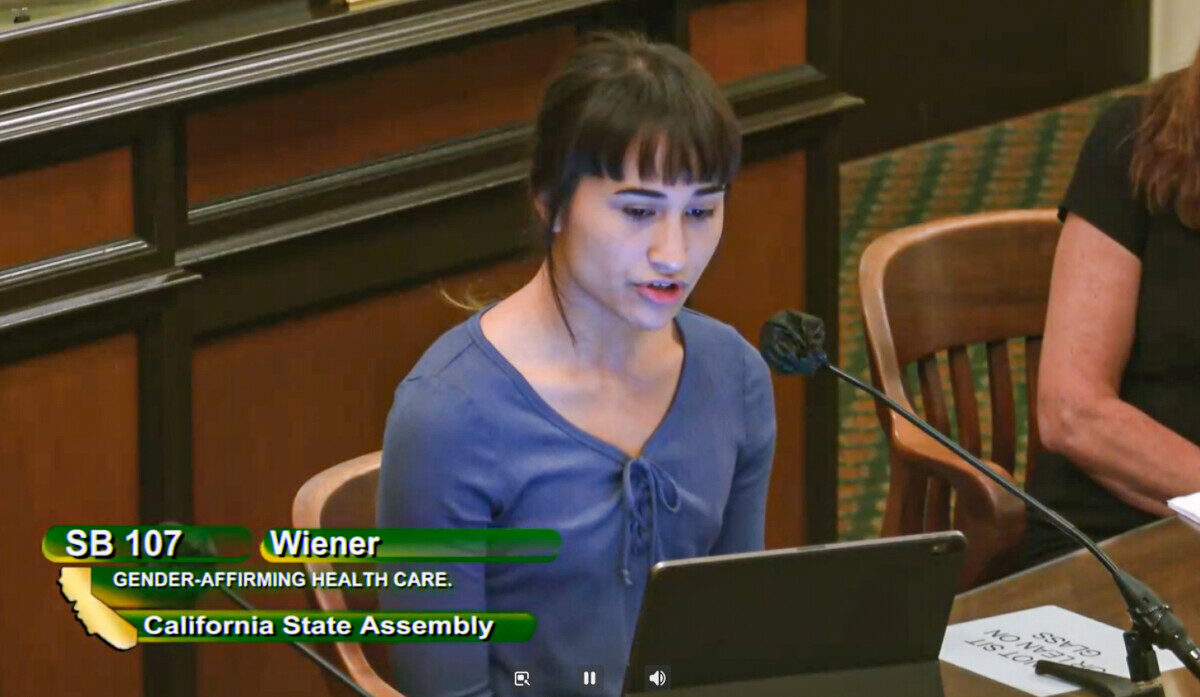

She recently testified against California Senate Bill 107, proposed legislation authored by Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco), that would shelter parents who consent to the use of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and gender transition surgery on their children from prosecution in other states that view such actions as child abuse.

“I think that is really dangerous for families across the U.S. It can tear families apart,” said Cole, who is expected to testify against the bill again this week.

Cole has been harassed on social media and received a couple of death threats from trans activists since she announced her detransition and took a stand against “gender-affirming” policies.

“Now that I’m completely disillusioned from all of it, it’s really shocking that we’ve even gotten to this point,” she said.

The Struggle

Diagnosed with ADHD at a young age, Cole now believes she’s “on the spectrum.”

“There is really a high comorbidity rate between gender dysphoria and autism,” she said.

Though “very feminine” as a young child, Cole was “a bit of a tomboy,” as she grew older.

“I just really hated dresses, skirts, and things of that sort,” she said.

Children’s TV shows had left her with the message “girls are less significant,” because they often depict characters who are more girly or feminine as “stupid, airheaded, and like just get in the way of things,” she said. “And that kind of imprinted on me.”

However, her real fear of femininity and early disdain for womanhood began years ago on social media and LGBT websites, she said.

“I had started puberty fairly young, about 9 years old, and I started to struggle with growing into a woman,” she said.

She started her first social media account at 11 on Instagram, and with nearly unrestricted access to the internet, she was exposed to inappropriate content, including pornography and “sexting” in online communities.

On Instagram, she was first approached by boys who identified as gay and bisexual through the platform’s messaging feature, but eventually began spending more time on recommended websites for 12- to 19-year-old “trans” teens.

“There was one particular page that stood out to me. It was a bunch of adolescents who identified as FTM [female to male]. It seemed like they were very closely knit, a very supportive community, and that just kind of spoke to me because I’ve always struggled with making friendships and feeling excluded. I’ve never really fit in with other kids my age.”

Cole seldom interacted with the transgender community in real life, but she noticed from online discussions with trans teens that many of them had deep emotional scars and mental health issues.

“Pretty much every transgender person I’ve ever met, especially around my age either has really bad family issues, or they’ve been sexually abused or assaulted at a very young age, and it’s really concerning that nobody really talks about that association,” she said.

At 11, Cole also didn’t understand she wasn’t supposed to look like the sexualized images of scantily clad women she saw online.

“I didn’t know that then,” she said. “I started to develop body image issues. I started thinking, ‘Why don’t I look like this? Am I not a woman?’ And a lot of the feminist content pushed by other girls was making womanhood out to be this terrible thing.”

The Transition

By the time she was 12, Cole told her parents she was transgender and they sought out professional medical help.

Cole went to a gender specialist, who referred her to an endocrinologist. When the endocrinologist refused to prescribe blockers or hormones, citing concerns about how they could affect Cole’s cognitive development, he became the first and last doctor to ever deny her gender-affirming care.

“It was very easy to just find another endocrinologist who would affirm me,” she said.

After two appointments, a second endocrinologist approved both puberty blockers and testosterone.

Cole was 13 when she began physically transitioning. The puberty blocker injections reduced the estrogen in her body, and about a month later, she started injecting herself with testosterone, a process medical professionals call hormone therapy.

“They put me on blockers first,” she said. “I would get hot flashes. They were pretty bad. They would happen kind of sporadically, and it would get to the point where it would feel really itchy. I couldn’t even wear pants or sweaters in the winter. It’s like an artificial menopause.”

Once on testosterone, Cole’s voice “dropped pretty low” and her breasts got smaller and lost their shape over time, she said.

Cole stayed on puberty blockers for about 18 months and testosterone for about three years.

The hot flashes ceased when she stopped taking the puberty blockers, she said.

Binding Decision

At school, Cole was “an awkward kid,” but had made a few more friends online and in person. But, because she had only come out to her closest friends, she had to deal with anxiety over the possibility of being outed.

“I never even told teachers my preferred name or anything up until high school, but I was presenting in men’s clothes and shorter haircuts,” she said.

A few months after she was prescribed testosterone, Cole was groped by a boy in the middle of her eighth-grade history class, which was so chaotic that no one noticed—including her teacher, she said. The incident sealed her decision to wear binders to flatten and conceal her breasts.

“I had a relatively small chest, but it still did a bit of damage to me. My ribs are a little deformed because of them. The way they work—it’s not like the breasts just disappear—they push the breast into the ribcage,” she said.

Cole recalls her binder sticking to her skin in the hot Central Valley California weather and her chest feeling constricted.

“It was just the most uncomfortable thing,” she said.

She used the men’s bathroom, but always feared she might be sexually assaulted.

However, she didn’t change in the boys’ locker room because she was afraid of being seen with her binder, and “that somebody would make a comment on it, and target me for it,” she said.

Most of the students, except those who had known her as a younger child, knew her as a male, but a boy in her Phys Ed class eventually noticed her feminine features.

“There was one time during P.E. when we were swimming. I took my shirt off. I was wearing a binder, and somebody pointed out my body shape. That was another thing that made me want to get rid of my breasts,” Cole said. “He said something along the line of, ‘I don’t know what it is, but you’re looking kind of feminine,’ and that kind of hurt me.”

Before the first day of her freshman year in high school, Cole went to the principal’s office with her parents and asked for her name and records to be changed to “Leo.”

‘Top Surgery’

Before her operation, Cole attended a “top surgery” class with about 15 other children and their parents to learn about the different types of incisions.

In hindsight, she said, “it kind of felt like propaganda—the words they use like ‘gender-affirming care’ and things of that sort,” she said. “It does feel like I was sold a product.”

Cole recalls looking around the room and noticing about half of the other kids appeared they were a few years younger than her.

“Looking back on it now is a little horrifying. It’s a little weird considering … they were already considering surgery,” she said.

But, at the time, seeing other kids and knowing she wasn’t alone, solidified Cole’s decision to go ahead with the most widely performed type of double mastectomy called a “double incision with nipple grafts” in June 2020. She was 15.

The surgery involved removing breast tissue and contouring the chest to make it look more masculine.

“They take off the nipple and reattach it in a more masculine position, and there are a few side effects associated with it,” Cole said.

Not only is there a loss of sensation from cutting away the breast tissue, but repositioning the nipple requires severing the duct that supplies breastmilk to the nipple, she said.

The surgery left Cole with deep muscle soreness for which she was prescribed an opioid-based medication, but because the pain from the resulting digestion problems was worse than the pain in her chest, she stopped taking the pills.

“I was actually disabled for a while. I had a really limited range of motion, especially in my arms and upper body. There were a lot of things I couldn’t do. I couldn’t even leave the house for a few weeks,” she said. “I remember that being really upsetting.”

The most devastating part of the recovery process has been ongoing post-op issues with her nipples, she said.

“It’s been two years, and I’m still having some really bad skin issues,” she said. “The way the skin heals over the grafts … is just awful. It’s really quite disgusting.”

Cole said she had trouble contacting her surgeon afterward, and although she was supposed to have a follow-up appointment with him, she ended up having a call with two nurses who were in the operating room instead.

She also worries the puberty blockers might have affected her brain development as her first endocrinologist had warned, but her greatest regret is how the surgery has permanently affected her as a woman.

“I was 15. You can’t exactly expect an adolescent to be making adult decisions,” she said. “So, because of a decision I made when I was kid, I can’t breastfeed my children in the future. It’s just a little concerning that this is being recommended to kids at the age I was, and now even younger. They’re starting to operate on preteens now.”

Detransition Dilemma

During the COVID-19 lockdowns and distance learning, Cole resorted to social media for virtual interaction and noticed girls her age were posting “super-idealized” pictures of themselves. Although she realized the images were edited and enhanced, they triggered the same body image issues she had experienced as a child.

“For a while it made me wonder, ‘Is this really a woman’s worth? If I don’t do this, does that make me not as good as these other women?’” she said.

But eventually, Cole bought some feminine clothing and makeup, which she only wore in the privacy of her room. “I guess subconsciously I started to realize like what I was losing started to miss presenting more femininely, like being pretty,” she said.

Over time, she grew increasingly more disillusioned with the idea of living as a man.

“I realized I wasn’t really up for a lot of the responsibilities that come with it,” she said. “There were times when I felt like I wasn’t good enough as a girl, but maybe I’m not good enough as a boy either, and maybe I just can’t be good enough to be either, so I don’t really know what I am.”

Over the next few months, the isolation of the lockdowns and school closures took their toll on Cole’s state of mind. She was depressed and fell into an emotional tailspin.

During the second semester of her junior year, Cole’s grades plummeted, and her parents decided to put her into an online-only school program.

“It was sort of like a homeschooling program, except I would have to go to the district office at least once per week for testing purposes,” she said. “My school performance actually got a lot worse, because now I was truly isolated.”

But Cole admits less social interaction gave her time for more introspection.

During the last quarter of her junior year, she took a psychology class for the first time and learned about child development. One of the lessons covered the Harlow experiments on infant rhesus monkeys with a theme of maternity, mother-child bonding, and breastfeeding.

“I started to realize this is what I’m taking away from myself. I’m not going to be able to bond with my children the same way that a mother does by taking on a male role and I’ve gotten rid of my breasts, so I can’t feed my children naturally or be involved with them in that way. And I think that was like the biggest catalyst in me realizing how wrong all of this was,” she said.

Embracing Womanhood

Cole announced her detransition in May 2021, about 11 months after the surgery, and has embraced womanhood.

“I am a woman,” she said.

Despite her transition, Cole said she has always been mainly attracted to masculine men and had only ever been “marginally attracted” to women. She is “straight,” she said, and knows now that her gender confusion as a child was based on insecurity and her fear of being a woman.

Cole has enjoyed “cultivating” a new feminine look for herself, but says she still isn’t really into makeup and doesn’t have time for it most days.

“I’m almost always in a dress or a skirt because, honestly, it’s really comfy,” she said.

She’s learned to accept her body the way it is, she said, and doesn’t want to go through the process of reconstructive surgery or get breast implants.

“There are multiple options for reconstruction, but I honestly don’t think it’s worth it,” she said. “I will never get the function back no matter what I do, so there’s not really a point in doing it.”

Cole graduated from high school in May and has applied for college.

Message of Hope

Though she has been harassed on social media and threatened by activists, Cole said she’s committed to sharing her story.

“I want to prevent more cases like mine from happening,” she said.

She wonders why educators have become complicit in the “gender-affirming” process.

“The problem is they’re not really pushing back on this whole trans thing. When I told the high school to change my name, and my email, and their records, there was really no pushback or anything,” she said.

Cole urged children who may be thinking about gender transition surgery “not to get caught up in the whole romanticization” of what it might be like to be the opposite gender and suggested they consider that there may be “other reasons” underlying gender dysphoria, including autism or other mental health issues.

“I very much suggest waiting, because the brain doesn’t stop developing for most people until about their mid-20s, if not a bit later, and teenagers are known for making rash decisions. It sucks hearing that, especially as a kid, but it’s the truth,” she said. “There is a reason why you can’t buy cigarettes or alcohol or vote or rent a car under a certain age.”