A boat sculpture with the words ‘As the sea dies, we die’ written on the sail is pictured during an Extinction Rebellion climate change protest on the beach in St Ives, Cornwall on June 11, 2021, on the first day of the three-day G7 summit being held from 11-13 June. (DANIEL LEAL-OLIVAS/AFP via Getty Images)

Labelling of virus lab leak theory as a conspiracy was shaped by influential figures with a conflict of interest; some see that as a lesson for other scientific debates

News Analysis

The way the discussion on the origin of COVID-19 was derailed by conspiracy labelling reminds environmental economist Ross McKitrick of the debate around climate change.

“There are ideas that were never disproven and actually have a lot of evidence to support them, but for political reasons and cultural reasons within the university they just aren’t looked at,” McKitrick, a professor at the University of Guelph, said in an interview.

As bias on a certain issue becomes structural, McKitrick says, it makes its way into government communications and even into “big tech” platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, which make editorial decisions—decisions they “have absolutely no business making” —to censor one side of the debate.

In the case of the virus, as more scientists and even U.S. President Joe Biden joined the chorus that the lab leak theory can’t be dismissed since a natural origin hasn’t been proven, many media and online platforms such as Facebook had to backtrack on their decision to censor the one side.

“We saw that play out over a period of around 12 months. Now what happens with the climate change issue, it’s the same thing, but it’s playing out over a much larger time frame,” McKitrick said.

Author and veteran science journalist Nicholas Wade was one of the earlier observers who noted that the virus origin discussion had been wrongly steered in a certain direction by influential figures in the scientific community.

The discussion, including in media reports, was mainly shaped by two articles published in two influential scientific journals, The Lancet and Nature, dismissing the lab leak theory as unscientific, with one of the articles labelling it a conspiracy theory.

Since then, it has come to light that Peter Daszak, the organizer of the Lancet article, which was published as an open letter, has ties to the Beijing-run lab researching coronaviruses in Wuhan, the epicentre of the virus outbreak. However, he didn’t disclose that connection in the letter. The Chinese regime, to avoid blame, has an obvious interest in denying any origin theory besides a natural one and has been vocal in denouncing any lab leak possibility.

As reported previously by The Epoch Times, documents released under freedom of information requests showed that the two articles appear to have been part of a co-ordinated effort originating from a February 2020 teleconference organized by Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Fauci, whose organization has funded research on coronaviruses at the Wuhan lab in the past, said early in the pandemic that there is evidence the virus had a natural origin. But he recently backtracked on his position as other members of the scientific and political community came forward to say the issue is not settled yet.

Wade, who was a staff member for The New York Times’ science pages for many years, as well as a writer and editor for Nature and Science, says that scientists rely on influential scientists and those in positions of power in academia to advance their careers, and often that could mean that those who see flaws in prevailing ideas advanced by influential figures are afraid to speak up.

“If you take an unpopular view that one of the leaders of your field or scientific establishment seem to oppose, then you’re putting your career at some risk,” Wade said in an interview.

“Given that, I suspect there may be other instances where a small group of scientists has influenced everyone else. Climate change is one possibility one might look at.”

Early in the pandemic, many media reports, including in Canada, referred to a “scientific consensus” on the virus being from a natural source. But Wade and McKitrick point out that science doesn’t work by consensus.

“Politics works by consensus and by counting votes, and science doesn’t, and shouldn’t,” Wade says.

‘Childish’

After the reversal in recognizing the lab leak theory as a valid hypothesis, some media that had actively labelled that possibility as a conspiracy theory interviewed experts on the issue. They justified the former stance by saying some scientists didn’t want to support the position of former U.S. president Donald Trump, who was very vocal in criticizing Beijing for the virus outbreak.

In one such article, CBC News quoted a scientist who said, “You don’t want to be seen to be contributing to the misinformation or to a toxic narrative that harms people.”

Wade says such arguments are “so childish.”

“I’m just amazed to hear this argument coming from the mouths of educated people who should know a lot better than that,” he said.

McKitrick says if scientists “lie to the public when it suits their political purposes,” the public would downgrade their trust in academic scientists and think that scientists are putting politics first, whether it’s the virus origin discussion or the climate change debate.

Ian Clark, professor emeritus of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Ottawa, agrees that politics have no place in science.

In the case of climate change, a field that Clark is involved in, there are different factors, he says, that have made the issue political. As an example, there are “geopolitics involved, with Russia and China supporting environmental movements, because it’s crippling Western democracies.”

The issue bears ever more importance as climate change is at the forefront of policy-making in Western countries, with the U.S., Canadian, and other governments enacting legislation to curb fossil fuel use and emissions, leading to major impacts on the economy and people’s daily lives and cost of living.

Fear of Speaking Up

Madhav Khandekar, a retired Environment Canada scientist with a PhD in meteorology, says many papers are being published in peer-reviewed journals questioning various assumptions linking human activities and climate change, but they’re not being taken note of by the media.

He himself has authored a number of such articles pointing out that climate is changing due to natural reasons rather than human activity, published in peer-reviewed journals such as Pure and Applied Geophysics.

“More and more scientists are now questioning some of the basic assumptions of global warming science,” Khandekar said in an interview.

But still, he says, many dare not speak publicly, especially younger scientists concerned about their career prospects.

William van Wijngaarden, a physics professor at York University who has studied climate change, has observed the same issue.

He told The Epoch Times that when he goes to conferences, there is a noticeable reluctance among attendees to publicly ask questions from the “non-politically correct side” of the issue. But it’s a different matter in private.

“When you talk to people one on one, when there’s no one else around, such as when having lunch with them, I’ve had a number of them say, ‘Please don’t tell the others I told you this, but I agree with you,’” said van Wijngaarden, who doesn’t believe anthropogenic global warming has been proven.

“There are very few people who have the courage to really stand up against this.”

Many of those holding contrarian views are also subjected to public character assassination. There are websites created by climate change activist organizations profiling those who are skeptical of the prevailing narrative, trying to cast these scientists in a negative light and discredit them.

Sticking to the Facts

Van Wijngaarden says in many cases those who want to shut down the scientific debate on climate change don’t have a strong background in the hard sciences and are more from the social sciences.

He points to the example of the discussion on carbon dioxide’s impact on global warming.

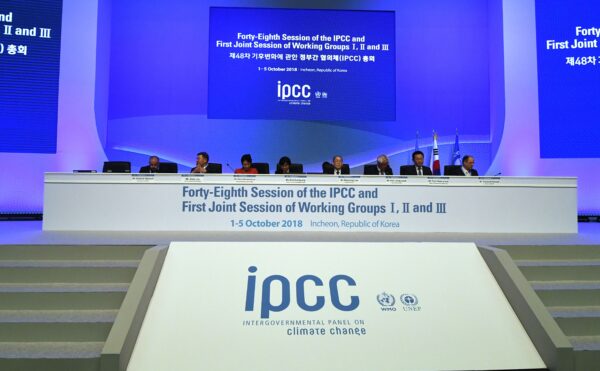

Delegates and experts attend the opening ceremony of the 48th session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in Incheon, South Korea, on Oct. 1, 2018.(Jung Yeon-Je/AFP via Getty Images)

As the world became more industrialized, carbon emissions from fossil fuels increased. Those who believe human activity is the cause of climate change say the emitted carbon dioxide leads to significant warming due to the greenhouse effect.

Van Wijngaarden says his own research shows that if carbon dioxide is doubled, there will be less than 1 degree Celsius warming, which he says is not very significant. The complication, however, comes from the fact that as it gets a little warmer, there will be more water evaporation, which amplifies the greenhouse gas effect, with the expectation being that there would be more warming. And that’s where the disagreement lies.

“That’s where things get murky. The measurements are not clear that the water vapour is increasing all that much,” he says, adding that it’s quite a complex issue due to different factors involved.

He says the scientific literature of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body that is the major driver of climate policy globally, has been saying that with this additional vapour factor, the warming will be amplified to 1.5 to 4.5 degrees Celsius.

That’s a huge error bar, van Wijngaarden says, adding that his own research results lie on the lower end of this margin.

He says almost all the models that are used in the climate science community to come up with these predictions run warm and have been seen to predict much more warming than what is actually observed.

“It’s very difficult to model the Earth’s climate. There’s a lot of things you have to take into account. Even the biggest supercomputers may not be powerful enough to handle it,” he says.

Given all these uncertainties and large error margins, van Wijngaarden says, it’s important that the scientific community sticks to the fundamentals of science and looks at all data objectively, rather than becoming defensive and ignoring the uncertainties.

Van Wijngaarden says there were many predictions in the late 1990s about massive temperature increases that were supposed to happen by now, but more than 20 years later, those predictions haven’t panned out.

“In the hardcore physics community, they would say you guys better be cautious about the claims and understand what you’re doing. But in the climate community, a lot of people have been rather naive, and I’d say have become defensive. That’s troubling to me,” he said.

In a book he wrote on climate change in 2016, van Wijngaarden notes that the IPCC acknowledged there were mistakes in its reports, such as a claim in its 2007 report that the Himalayan glaciers would be completely melted by 2035. He questions why, if the scientific work is conducted with input from over 2,500 scientists and experts, these mistakes are not caught. The answer, he says, is that the different parts of the report were written by small subcommittees, and the report as a whole was only reviewed by a small number of individuals.

Models

Khandekar agrees that almost all models used in the field predict more warming than warranted by reality. He says he has seen it first-hand, using data from decades past to produce forecasts for the present and finding the results to be much warmer than what was actually recorded.

“I have lost my faith in climate models,” he says.

McKitrick says that based on the social media postings of many of the scientists creating the models, it’s clear that many of them are environmentalists, “so they may not want to be seen running a model or saying anything that might dissent from the climate emergency campaign we’re seeing.”

But he and Khandekar point out that there are models developed in Russia, where scientists are presumably more disconnected from the community in the West, that don’t predict as much warming.

Clark notes that results from a Russian model are closest to the measured global temperatures from satellite records. He wants to see a new report coming out by the IPCC in 2022 to see if there have been improvements to the models.

Steering the Research

Among the arguments used to dismiss scientific findings refuting anthropogenic global warming is that the vast majority of published work on the issue agrees that climate change is due to human activity.

Besides the fact that science doesn’t work by consensus, McKitrick notes that a lot of research is steered in one direction by the grants that are provided.

He says many government grant competitions in Canada, for example, don’t start off by questioning the science linking human activity to climate change, but take it for granted that there’s a crisis and ask how emissions should be reduced quickly.

“It’s very difficult to get funding for something on the climate issues,” McKitrick says, adding that the funding bias “puts a filter in place where there’s a non-stop supply of studies that will find some element of the natural world is suffering due to climate change.”

‘Ambulance Chasing’

McKitrick, who maintains that climate is changing due to factors beyond human activity, says it’s “odd” that there are no news stories about how climate change is having a beneficial effect, such as more greening.

“If the story was in the other direction, if we were in a cooling trend, you’d expect to see a lot of stories about how global cooling is going to be harmful to ecosystems,” he says.

He adds that there’s a lot of “ambulance chasing,” with people wanting to show that they somehow explained or predicted a phenomenon.

This is commonly seen following heat waves, such as the recent one in Western Canada and the Western United States, where some scientists commented that greenhouse gases are significantly exacerbating the warmer temperatures.

“They always appear after something’s happened and say, well, this is consistent with what we were expecting, but they can’t predict an event ahead of time,” he says.

“It’s a kind of problem that is completely unfalsifiable, as it’s not a science that you can ever test. It’s not a theory you can have an experiment to see whether it’s true or not.”

Driving Factors

Van Wijngaarden, who describes himself as a political liberal, says he got into the field of climate change with the motivation to defend “poor Al Gore,” whom he thought was being targeted by conservatives for his environmental activism.

“I fully expected that I would decide on this in the Al Gore camp. Then I started to look at the data and the claims made, and the claims are just silly,” he said.

He thinks a major factor contributing to the bias of many in the field who link climate change to human activity is that many people in the mid- to late-20th century started to develop a “heightened awareness of pollution” for good reason, against the backdrop of issues such as plastics ending up in oceans and oil spills impacting the ecosystem.

“I think a lot of us, myself included, became very much environmentalists,” he says.

When theories linking human activity and global warming emerged in the 1990s, given the state of mind of many environmentalists, it was easy for people to agree that that was the case, since there was already an understanding that “we’ve been treating the environment so badly,” he says.

McKitrick adds that the movement is fuelled by major political factors behind the scenes.

Pointing to the net-zero emission goals by 2050 pushed by international bodies and adopted in many countries including Canada, he says he finds the timeline to have a “remarkable coincidence” with China’s 2049 initiative—the ambition of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to become the world’s dominating player by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

“The two are really pointing in the same direction,” McKitrick said.

“By the middle of this century, the West will have seriously weakened itself and demolished its own industrial strength and access to energy and other things that have historically made it strong and prosperous, and at the same time, we’ve got CCP-led China massively expanding its fossil energy infrastructure at home and around the world and pursuing its expansionist ambitions.”

That’s why he’s concerned about the many 2050 net-zero initiatives that he says have no basis in scientific fact and will cripple the economy.

“One of the really disturbing aspects of Western policy is the number of financial institutions that are cutting off all funding for oil- and gas- and coal-related developments,” he says.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping votes on changes to Hong Kong’s election system during the closing session of the National People’s Congress at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China on March 11, 2021. (Nicolas Asfouri/AFP via Getty Images)

This not only impacts the domestic economy in these Western countries, but it creates an environment where developing countries that need infrastructure for energy projects can no longer go to Western-based international banks. Instead, they will have to rely on China and become indebted to its debt-diplomacy mechanisms, such as the Belt and Road Initiative, resulting in being exploited by Beijing, he says.

McKitrick also notes that the environmental groups that are instrumental in pushing for climate policies in Western countries are notorious for being silent on China’s environmental performance. He puts this down to Beijing’s influence operations in the West.

This is exacerbated by major financial institutions that are desperate for more business in China. These Wall Street giants cut funding for energy projects in the West in the name of climate activism and social responsibility, but expand their energy funding projects in China, he says.

Beyond issues of geopolitics and influence operations, he notes that the climate change movement has also reached a point in Western countries that it has become a “transcendent cause.”

“It’s an area where there is a huge amount of data and it’s not all that difficult to look things up. But what I encounter with students is that they’ve got very strong opinions on the environment, but almost no actual information about it as often it comes as a surprise for them to see, for instance, how much the environment has improved in Canada and the United States,” he says.

“It’s more of a belief system and a moral code than a scientific issue for them, and I think that contributes to the fervour of the issue. People just begin to think that your attitude towards carbon dioxide emissions is the marker of whether you’re a good person or not.”

Seeing a general trend in society, politicians cater to these sentiments for political scores and votes, he says.

Influential Figures

Clark says the theory of linking human activity to climate change has been solidified in the West by a few influential figures.

He gives a few names as examples.

One is Michael Mann, currently director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University. Mann’s work along with two colleagues in the late 1990s is behind the famous “hockey stick” graph that shows temperatures from the year 1000 to the 2000s, demonstrating dramatic rises in temperature starting around the industrial era. The graph was featured in Al Gore’s 2006 film “An Inconvenient Truth.”

The graph has been disputed in the scientific community, including in a paper co-authored by McKitrick that showed a period of warming around the 15th century that was warmer than that in recent times. The paper noted natural variations in climate over time, with scientists pointing to different factors contributing to the temperature variations.

Nonetheless, Clark says Mann’s work, which to him is “patently wrong,” has been used to convince many politicians and young people that the Earth is heating up due to carbon dioxide.

The Epoch Times asked Mann for an interview but didn’t hear back.

Clark says James Hansen, who was the director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), is another influential figure leading to NASA’s activism on the issue. Since retirement, Hansen has joined Columbia University’s Earth Institute as an adjunct professor and has been arrested on a few occasions during environmental protests for obstructing traffic and police.

“He has his career staked on this, so he can’t do anything but pronounce on global warming,” Clark says.

The Epoch Times contacted Hansen for comment but didn’t hear back.

The issue of NASA’s activism on climate change was derided by 49 former NASA scientists and astronauts in a letter in 2012, asking that NASA and GISS “refrain from including unproven remarks in public releases and websites.”

“We believe the claims by NASA and GISS, that man-made carbon dioxide is having a catastrophic impact on global climate change, are not substantiated, especially when considering thousands of years of empirical data,” the letter said.

“With hundreds of well-known climate scientists and tens of thousands of other scientists publicly declaring their disbelief in the catastrophic forecasts, coming particularly from the GISS leadership, it is clear that the science is NOT settled.”

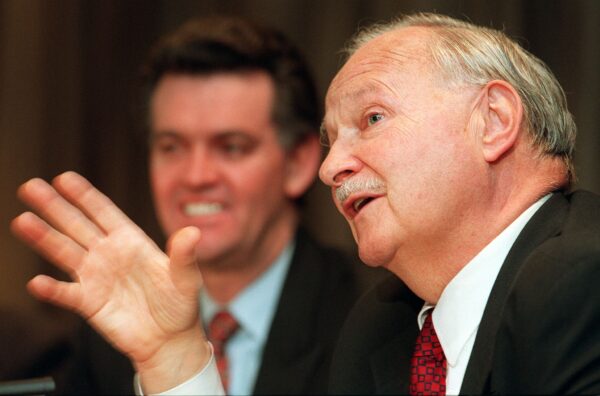

On the political side, one of the most influential figures was Maurice Strong, who Clark says managed to get very powerful people involved in the cause.

Strong, a Canadian business executive, held key positions in the United Nations, including as under-secretary-general of the international body.

Strong was the founder of the United Nations Environment Program and organized key UN conferences on the environment. He also initiated the first international expert group meeting on climate change.

Strong has had major links to China, through the business corporations he was involved in and later in his UN work, and moved to Beijing upon retirement where he lived until his death.

Clark says the onus is on the media to report objectively on the issue, but too many seem to be following an agenda and give voice to those who want to push one side of this issue.

He says the insufficiently challenged green movement has now morphed into a major political force, with governments formulating policies based on unfounded science that have major implications for people’s lives, and offering incentives for newer technologies that could have even worse environmental impacts.

“What people hear all the time is heat dome and wildfires are all because of CO2, and people don’t have the science literature, but the idea that we can dial it back if we just turn down CO2 emissions is absurd if you understand the carbon cycle and climate,” he said.

“But that’s what people hear, and that’s what they vote for, and here we are with carbon taxes.”

He says it’s important that people be presented with the facts and for the media to pursue the objective truth.

“To use the old analogy from the ‘Wizard of Oz,’ we need to pull back the curtain and expose the man behind the curtain.”