Chinese home-made airship AS700 takes off for a test flight at Jingmen Zhanghe Airport in Jingmen, Hubei Province of China, on Sept. 16, 2022. (Shen Ling/VCG via Getty Images)

By

Years before a gigantic white spy balloon from China captured America’s attention, a top Chinese aerospace scientist was keenly tracking the path of an unmanned airship making its way across the globe.

On a real-time map, the white blimp appeared as a blinking red dot, although in real life its size was formidable, weighing several tons and measuring 328 feet (100 meters) in length—about 80 feet longer than a Boeing 747-8, one of the largest passenger aircraft in the world.

“Look, here’s America,” the vessel’s chief architect, Wu Zhe, told the state-run newspaper Nanfang Daily. He excitedly pointed to a red line marking the airship’s journey at about 65,000 feet in the air, noting that in 2019, that flight was setting a world record.

Named “Cloud Chaser,” the airship had been flying for just shy of a month over three oceans and three continents, including what appears to be Florida. At the time of Wu’s interview in August, the airship was hovering above the Pacific Ocean, days away from completing its mission.

Wu, a veteran aerospace researcher, has played a key role in advancing the Chinese regime in what it describes as the “near space” race, referring to the layer of the atmosphere sitting between 12 and 62 miles above the earth. This region, which is too high for jets but too low for satellites, had been deemed ripe for exploitation in the regime’s bid to achieve military dominance.

Despite having existed for decades, the regime’s military balloon program came into the spotlight recently when the United States shot down a high-altitude surveillance balloon that drifted across the country for a week and hovered above multiple sensitive U.S. military sites. That balloon, the size of three buses, was smaller than Cloud Chaser.

The U.S. and Canadian militaries have since taken down three flying objects over North American airspace, although President Joe Biden on Feb. 16 said those are likely linked to private companies.

The suspected Chinese spy balloon drifts to the ocean after being shot down off the coast in Surfside Beach, S.C., on Feb. 4, 2023. (Randall Hill/Reuters)

Wu is turning 66 this month. He has ties to at least four of the six Chinese entities Washington recently sanctioned for supporting Beijing’s sprawling military balloon program, which the U.S. administration said has reached over 40 countries on five continents.

As a specialist in aircraft design, Wu has helped develop the Chinese regime’s homegrown fighter jets and stealth technology during his more than three decades in the aerospace field, taking home at least one award for his contribution to the military.

He was the vice president at Beihang University in Beijing, a prestigious state-run aeronautics school, until he voluntarily gave up the title for teaching and research in 2004, and he once served on the scientific advisory committee for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Armaments Department, a now-dissolved agency in charge of equipping the Chinese military.

Public records show that Wu is well-connected in the aerospace field, with stakes in many aviation firms. He is the chairman of Beijing-based Eagles Men Aviation Science, one of the six firms that, along with its branch in Shanxi, Washington has named as culprits in the balloon sanctions.

Both Beihang and the Harbin Institute of Technology, Wu’s alma mater and dubbed “China’s MIT,” are on a U.S. trade blacklist, the former for aiding China’s military rocket and unmanned air vehicle systems, and the latter for using U.S. technology to support Chinese missile programs.

‘Silent Killer’

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long vied for dominance in near space, which Chinese scientists see as a region for a variety of applications, from high-altitude balloons to hypersonic missiles.

From high above, there’s a wealth of information that an aerostat, equipped with an electronic surveillance system, can intercept and turn into an intelligence asset.

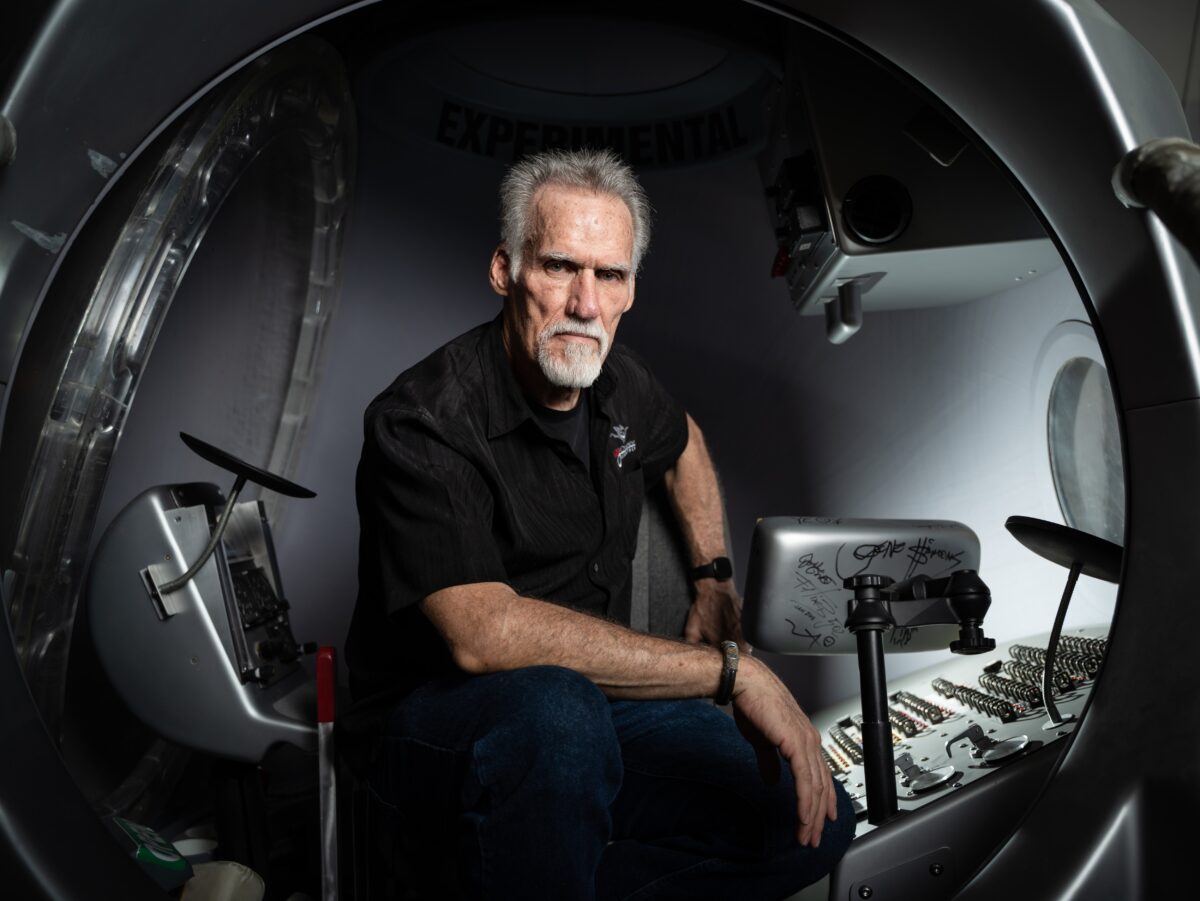

“If you’re flying a balloon that is 100,000 feet up in the air, you’ve got … visibility on the ground of hundreds and hundreds of miles over several states, because it’s up so high,” said Art Thompson, co-founder of California aerospace company Sage Cheshire Aerospace. During his three decades in the aerospace industry, Thomspon has worked on the B-2 stealth bomber and was technical director for the Red Bull Stratos project that broke the record for the highest balloon flight and the largest manned balloon.

Art Thompson, CEO of Sage Cheshire and president of A2ZFX, sits inside a model capsule he built for Red Bull Stratos in Lancaster, Calif., on Aug. 13, 2022. (Samira Bouaou/The Epoch Times)

“Whether it’s phone data, radio data, transmissions from aircraft, as to what the airplanes are, who owns it, all that data is available,” Thompson said.

As early as the 1970s, efforts were underway at the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences to explore high-altitude balloons, according to a state media report. Lacking the aid of computers, Chinese researchers drew inspiration from German and Japanese aerospace books and cut up newspapers to piece together prototypes.

The result was a helium balloon with an aluminum basket, altogether about the size of a typical hot air balloon. The team triumphantly named it HAPI and flew it into the stratosphere in 1983 to observe signals from a neutron star.

For the Chinese military, there’s high strategic value in aerostats, a technology that was in use as early as the late 1700s by the French as lookouts. Compared to airplanes or satellites, balloons are cheaper and easier to maneuver, can carry heavier payloads and cover a wider area, and are harder to detect, two regular columnists wrote in a 2021 article for PLA Daily, the Chinese military’s official newspaper. They consume less energy, allowing them to loiter in a target area for an extended period. And critically, they are often not caught by radars, so they can easily evade an enemy’s air defense system or be classified as UFOs.

A jet flies by a suspected Chinese spy balloon as it floats off the coast in Surfside Beach, South Carolina, on Feb. 4, 2023. (Randall Hill/Reuters)

Indeed, that appears to have occurred. Biden administration officials said they were able to retroactively detect three Chinese spy balloons that traveled over the United States during the Trump administration, and another after Biden took office.

Both Taiwan and Japan have since identified several suspected Chinese balloon incursions in recent years and are now threatening to shoot down any suspected objects in their airspace.

Chinese military researchers have also touted the utility of these balloons during combat. Newspaper articles and research papers have pored over balloons’ potential to screen for missiles, planes, and warships in lower space, serve as a medium for wartime communications, drop weapons to attack enemies, conduct electromagnetic interference, and deliver food or military supplies over a long distance.

U.S. Navy sailors assigned to Assault Craft Unit 4 prepare material recovered in the Atlantic Ocean from a high-altitude Chinese balloon shot down by the U.S. Air Force off the coast of South Carolina after docking in Virginia Beach, Virginia for transport to federal agents at Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek on Feb. 13, 2023. (Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Ryan Seelbach/U.S. Navy/Handout via Reuters)

“In the future, balloon platforms may become like submarines in the deep sea: a silent killer that invokes terror,” the military columnists said.

Such statements are not hyperbolic, according to Thompson. Paradoxically, the slow pace of a balloon, when used well, is in fact its strength.

“It’s virtually invisible on radar,” said Thompson. While people may be concerned about an intercontinental missile flying over, which would take several minutes, a balloon could transport one discreetly without being detected.

“Now when you decide to release that missile, it doesn’t take several minutes—it takes only a matter of seconds,” he added. “We can’t respond fast enough … It would hit us before we’d know what happened.”

“It’s a scary scenario. It’s funny that one of the oldest technologies is potentially also very dangerous.”

A Thriving Industry

Chinese scientists have made great strides in near-space technology since HAPI’s launch. In 2017, they sent a yellow-spotted river turtle 68,900 feet over the northwestern Xinjiang region, marking the first time an aerostat was able to bring a live animal into the stratosphere.

The following year, a high-altitude balloon dropped three hypersonic missiles in the Gobi Desert in Inner Mongolia. Last year, a balloon brought a rocket more than 82,000 feet above the earth, making China the first country experimenting with such techniques, according to state media reports.

While the Chinese regime claimed the spy balloon was a civilian airship used for meteorological purposes, meteorological officials in China have a history of collaboration with the military.

Meteorological officials under the PLA in 2013 coordinated with local meteorological bureaus to host a three-city military drill, according to state media outlet Xinhua. Such cooperation appeared to have deepened in the following years after CCP leader Xi Jinping ordered a major overhaul of the military. In 2017, the director of the China Meteorological Administration, the country’s national weather service, met with officials in the military and vowed to make a priority of “military-civil fusion,” a term for the regime’s aggressive national strategy to harness private sector innovations for military use.

The manufacturing of balloons has also flourished in the meantime.

Zhuzhou Rubber Research & Design Institute in China’s south-central Hunan Province, a subsidiary of state agrochemical giant ChemChina—which is on a U.S. blacklist over its ties to the military—is a dedicated supplier for the national weather bureau, producing three-quarters of the balloons it uses in nationwide weather stations, according to state media reports.

The company, sometimes described as a “made-in-China hidden champion,” was millions in debt in the early 2000s until it entered the balloon manufacturing game. It went on to become a leader in the industry, playing a chief role in formulating China’s national standard for weather balloons, and has around 30 patents under its name, a local government website shows.

In September 2017, Zhuzhou Rubber invested 30 million yuan ($4.38 million) in a key provincial-level lab for near-space sounding balloon research that it said aims to provide “security for national defenses on the near space front.”

It won a proclamation from the PLA’s General Armaments Department for designing a balloon for the return of Chang’e 5, the spacecraft used for China’s fifth lunar exploration mission, which was undertaken in 2020.

A Long March-5 rocket carrying Chang’e-5 spacecraft blasts off from Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site in Wenchang, Hainan Province of China, on Nov. 24, 2020. (VCG/VCG via Getty Images)

In March 2022, the China Ordnance Industry Experiment and Testing Institute—whose parent company, state-owned Norinco, is a major weapons producer for the Chinese military—inquired into prices for obtaining hundreds of sounding balloons from the firm, according to a tender bid on a Hunan provincial government site. It is unclear whether the institute made a bid after the tender.

The company’s website has become inaccessible since the recent spy balloon incident.

For the Chinese, these balloons are inexpensive tools for testing components for military equipment, Thompson said.

“They may be looking at as a particular piece of electronics that they want to put in a missile: is it going to hold up to the temperatures and altitude, or is it going to transmit,” he said. “So they might take that component that later is going to go on a piece of weaponry, and fly it to the altitude under a balloon to see how it handles it.”

‘China Speed’

Zhuzhou Rubber is but one player in the field. Dongguan Lingkong Remote Sensing Technology has claimed dozens of patents related to stratosphere aircraft, including a maneuverable stratospheric balloon and lightweight high-strength aerostat material. Wu is the statutory auditor of Dongguan Lingkong and the director of Beihang University’s Dongguan city research institute, which owns the company.

China Electronics Technology Group Corp. (CETC), a massive state-owned enterprise whose 48th research institute was hit with U.S. sanctions in the aftermath of the balloon incident, once credited itself for helping China bridge the technological gap in aerostats.

In 2010, the company showcased a large white blimp. Through its high-definition surveillance gear that scans the ground nonstop, it could spot details of objects as small as a book over an area of more than a hundred square miles, according to a Chinese state media report republished on the State Administration of Science website.

Their latest, the JY-400 balloon that CETC’s 38th research institute unveiled in 2021, can meet both civilian and military needs, with the capacity to carry payloads for detecting missiles and eavesdropping on and interfering with communications, Chinese media reports said. The reports cited Russian media expressing surprise at seeing their country outcompeted by China at a breathtaking pace, dubbing it “China speed.”

Thompson was struck by the JY-400 balloon’s visual resemblance to a U.S. military design, called the “Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System.”

That system was an Army program designed in 1998 by Raytheon that provides 360-degree surveillance to track low-flying cruise missiles, unmanned aircraft, and other threats. The dirigible had a synthetic aperture radar attached to its bottom. The U.S. Army began investing in it in the 2010s but ultimately discontinued funding in 2017, two years after one of the program’s two blimps broke loose and caused massive power outages in Pennsylvania.

A China Electronics Technology Group Corp. (CETC) aerial blimp hangs in display at the China International Aviation & Aerospace Exhibition in Zhuhai, China, on Oct. 31, 2016. (Qilai Shen/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Putting the two side by side, “you’d think they’re made by the same company,” Thompson said, noting that the only difference is one has the Chinese writing on it.

Thompson said it’s possible that the Chinese copied the designs of U.S. airships and adjusted certain parts, like the materials and size, to suit its needs.

Raytheon and CETC didn’t immediately respond to queries from The Epoch Times.

Wu’s Cloud Chaser airship was launched near Hainan, the island province that lies in the southern tip of China that U.S. officials have identified as a base for the Chinese surveillance balloon operations.

Considering China’s vast espionage program, those sanctioned by the United States represent only the “tip of the iceberg,” said Su Tze-yun, director of the Institute for National Defense and Security Research in Taiwan.

But challenges abound for Western nations seeking to blunt the covert operation. The regime, as Su noted, could easily use front companies as a cover to steal or import Western technologies while attracting little notice. Under the civil-military fusion strategy, every private company could be indirectly supporting the regime’s military development, making it harder to draw the line and impose punishment. But that at least heightens the need to block Chinese entities from acquiring U.S. firms, he said.

While Western countries are also developing balloon technology, what differentiates the actions is China’s authoritarianism, according to Su.

“Democratic countries are bound by law from infringing other nations’ airspace,” he told The Epoch Times. “This is why the same technology, once it’s in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party, would become a threat.”

Luo Ya and Dorothy Li contributed to this report.