Physician-scientist discusses China’s risky research, how samples from Canada may be used, and potential detrimental consequences

The P4 laboratory on the campus of the Wuhan Institute of Virology in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, on May 13, 2020. (Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

The SARS outbreak of the early 2000s that infected thousands worldwide and killed many was a learning moment for Beijing on how dangerous such viruses can be, says physician-scientist and author Dr. Steven Quay.

“They began to see these as potential bioweapons,” Dr. Quay, previously on the faculty of Stanford University’s School of Medicine and now CEO of Atossa Therapeutics, told The Epoch Times.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Quay fears the next pandemic could be magnitudes more deadly if risky research on the Nipah virus at laboratories like the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) continues unabated.

“If you can create a vaccine for your own population before you release it, … you can really have a differential effect. And they’re economic weapons, and they’re weapons of fear,” he said.

Dr. Quay says there’s evidence that China is engaged in highly risky lab engineering of the Nipah virus. Some of the evidence includes data from the WIV, while another aspect has to do with the shipment of deadly virus samples from Canada’s high-security lab in Winnipeg to China, he says.

Nipah, which can be transmitted from animals such as bats or pigs to humans, has a very high fatality rate, ranging between 40 percent to 75 percent. There have been a few known outbreaks of the virus, all of which occurred in Asia.

Dr. Quay says if human-to-human transmission of Nipah is made easier by researchers, the result will be disastrous.

“If they make it aerosolized, we are done as a civilization,” he says.

Sean Lin, Ph.D., former virology lab director at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Maryland, says he is highly concerned by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) focus on Nipah.

“People who get Nipah can have neuropathic syndromes. They can have severe brain damage. But they don’t die immediately, not like Ebola. So the virus can have a better chance to further propagate from the infected host,” Mr. Lin, a contributor to The Epoch Times, said in an interview.

“If the host can last longer and spread it more in human-to-human transmission, it would be a better bioweapon. That’s why the CCP is very interested in the Nipah virus, and that’s why I think it’s very dangerous.”

American microbiologist Richard Ebright agrees that research to enhance lethal levels or transmissibility (gain-of-function) of Nipah virus should be forbidden given the risks involved.

“Gain-of-function research and enhanced potential pandemic pathogen research on Hennipah viruses pose unacceptably high risks. Such research should be prohibited. Both in the US and overseas,” Mr. Ebright, a board of governors professor of chemistry and chemical biology at the Rutgers-New Brunswick School of Arts and Sciences, wrote in an email. Nipah is a type of Henipah virus.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention includes the Nipah virus on the list of potential bioterrorism agents that the U.S. government needs to be prepared for with the highest priority.

Security personnel stand guard outside the Wuhan Institute of Virology as members of the WHO team investigating the origins of the COVID-19 coronavirus make a visit to the institute on Feb. 3, 2021. (Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

The Evidence

Dr. Quay’s assessment of WIV’s involvement in risky Nipah research is based on raw data the lab researchers included in a published paper.

The paper’s main focus was examining early COVID-19 patients in December 2019, but the raw data included 20 unexpected items that showed up due to cross-contamination from other WIV research, he said.

For 19 of those items, such as honeysuckle genes, Dr. Quay was able to find corresponding papers published by the WIV, confirming that the lab was engaged in research on them and that the WIV was willing to publicly admit to working on them. But for one of the items he found—the Nipah virus—there was no published paper.

“They weren’t just pieces of the virus, they were pieces of the virus in what’s called an infectious cloning format,” he said.

Using the handle of a frying pan as a metaphor, Dr. Quay said the virus was found with synthetic biology “handles” that allow “moving genes around.”

“We found the Nipah virus in these handles that are very typically used for making infectious clones. This is completely against all bio-weapons conventions,” he said.

The other piece of the puzzle for the researcher is the fact that the National Microbiology Lab (NML) in Winnipeg shipped Nipah and Ebola strains to the WIV in March 2019.

The transfer was facilitated by former NML scientist Xiangguo Qiu, who was later fired from the lab along with her husband and fellow scientist Keding Cheng for having undisclosed ties to the Chinese regime and military. One of the concerns flagged by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) was that Ms. Qiu collaborated with senior Chinese generals in charge of biodefence and bioterrorism research.

Dr. Quay initially didn’t know if the Canadian samples were used in the same risky research. But he later observed that the Nipah strain he had found at the WIV was the Bangladesh strain. And one of the strains that Canada had sent to the Wuhan lab was also the Bangladesh strain.

“I spent about three hours combing the genomes of the two to be absolutely sure that they are identical, and they are identical,” he said.

“It goes March 2019 to the WIV. It would take one or two or three weeks to get it into a vector, and I find it in a vector in December 2019 from the laboratory. That’s perfect timing.”

Another indicator for Dr. Quay is a 2019 presentation by Shi Zhengli, a director at the WIV who is often called the “bat lady” for her work on bat coronaviruses.

Dr. Quay says Ms. Shi’s presentation at the Nipah Virus International Conference in Singapore, held Dec. 9–11 that year, showed China’s involvement in Nipah research.

“So there are three pieces of evidence: Canada ships to WIV in March [2019]. I find vectorized, gain-of-function, synthetic biology Nipah in December. And Shi’s [presentation] at a conference in December talking about doing work on Nipah,” he says.

Mr. Lin says the fact that Ms. Qiu, the fired Winnipeg lab scientist, risked attracting so much attention by facilitating the shipment of the viruses to the WIV shows how important they were to China.

“It means the CCP is interested in such a highly pathogenic Nipah virus,” he said.

Although the virus strains were shipped with the approval of the lab management, opposition parties and the current public safety minister have said they were surprised to learn of the shipment.

The Public Health Agency of Canada, which oversees the NML, previously told The Epoch Times that the shipments were done following the appropriate procedures and protocols.

Mr. Lin says research centres and governments in the West shouldn’t treat the Chinese research centres like any other academic institutes, as they are beholden to the Chinese military.

“Under the CCP’s military-civil fusion mechanisms, many research institutes can easily couple with military missions,” he said.

‘Aggressively Testing’

In 2012, China reported cases of a Nipah-like virus in miners in the south of the country. The virus was labelled the Mojiang virus, after the Mojiang County in Yunnan Province, where the mine is located.

The mine became more famous after the pandemic as it became known that WIV’s Ms. Shi discovered the coronavirus RaTG13 from bats in the same mine in 2013. Mr. Lin notes that RaTG13 is very close to the SARS-COV-2 which caused the COVID-19 pandemic. He adds that the Chinese regime prevents outside scientists and journalists to conduct further investigations in the mine.

In 2022, another species of the Henipah family, this one called the Langya virus, was found in the Chinese provinces of Shandong and Henan. Mr. Lin says this virus was the closest to the Mojiang virus, rather than the Nipah or Hendra viruses, which are the more commonly known Henipa viruses.

According to a paper by Chinese scientists working on the case, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, in nine of the 35 patients infected with the Langya virus, other pathogens were detected as well. These included Hantavirus and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV). Mr. Lin notes that while Hantavirus and SFTSV have become endemic in Shandong and Henan, it’s still very unusual to find all three viruses in a small sample size. He also notes that the viruses are very deadly, yet none of the patients died as a result of the infections.

“My suspicion is that the CCP is setting up some field-testing of different rare viruses to see which one can cause animal transmission and then further spread to humans, because it’s very rare for humans to co-infect with two or three rare viruses,” Mr. Lin says.

It adds to his suspicion that the key authors of the paper are from the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, also known as Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, which is under the People’s Liberation Army.

“I think the CCP is very aggressively testing different versions of the Henipah virus to see if there are any further adaptation of this virus to human infection,” he says.

‘Civilization Stops’

When the Black Plague happened in the 14th century, it set Europe back by 250 years, Dr. Quay says.

In the modern world, if a pandemic is so severe that it leads to a significant loss of the population, along with breakage of critical food and energy supply chains, disruption to transportation, and loss of police, fire, and hospital services, “civilization stops,” he says.

This could come about with a pandemic caused by a virus that has 50 percent or more lethality, he adds.

“SARS-CoV-2 had less than 1 percent [fatality]. So they’re working on influenza, they’re working on Nipah, they’re working on MERS. All of those are 30 to 70 percent lethal.”

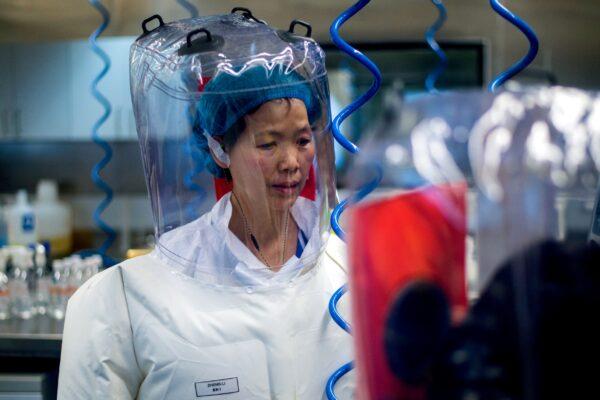

Chinese virologist Shi Zhengli is seen inside the P4 laboratory in Wuhan, China, on Feb. 23, 2017. (Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images)

Higher Risk

Dr. Quay says that since the COVID-19 pandemic, more countries have launched labs to research viruses, and this adds to the concern of outbreaks occurring if risky research is taking place.

“We have 50 percent more laboratories doing this kind of dangerous work around the world, and more than half of them are in countries that the United Nations has defined as politically unstable,” he says.

“What does that mean? Well, if there’s a civil war or if there’s a takeover, suddenly a laboratory with all these pathogens comes under the control of people that maybe shouldn’t have it.”

Mr. Lin agrees that the proliferation of risky research on deadly pathogens poses a great danger.

“People are doing more and more dangerous experiments with the progress of biotechnology, genetic engineering technology,” he says.

“We need to be very alert to the danger of emerging pathogens. One aspect is the more frequent, emerging viruses in nature, and the second part is the bioweapon interest of the CCP or other terrorist groups. These are very dangerous situations.”